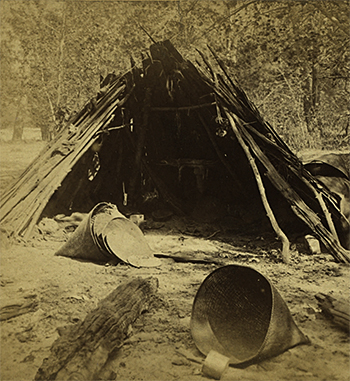

Miwok natives from the western Sierra Nevada foothills and Paiutes from the east side of the mountains were the first to visit the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Hetch Hetchy was the location of late summer and fall encampments for the purpose of gathering food for the winter. Black oaks that dotted the valley floor supplied acorns for meal. A variety of berries, roots and seeds were gathered (the name Hetch Hetchy is a Miwok word for a type of grass in the valley from which seed was harvested1). And deer came down into the valley in large numbers as the acorns began to fall. Despite incursions by white Americans, Indian use of the valley in this manner continued into the 20th century.

White miners and settlers began to move into the region with the discovery of gold in California in 1848. The first known European American visit to Hetch Hetchy was by Joseph Screech and his brother in 1850. Screech reported that:

- ... up to a very recent date, this valley was disputed ground between the Pah Utah Indians from the eastern slope and the Big Creek Indians from the western slope of the Sierras; they had several fights, in which the Pah Utahs proved victorious.2

Use of the valley by non native Californians was largely in the form of summer pasture for sheep into the 1890s. John Muir, whose own experience in the Sierras began as a shepherd, noted that:

-

Sheep are driven into Hetch Hetchy every spring, about the same time that a nearly equal number of tourists are driven into Yosemite; another coincident which is remarkably suggestive.3

When the U.S. Calvary was given responsibility for protecting the new Yosemite National Park beginning in 1891 Hetch Hetchy became a gateway out of the Sierras as troopers would escort shepherds in one direction and their sheep in another across the mountains.

Tourist travel to Hetch Hetchy was limited because of the isolation of the valley. Impressions, though, by those who did visit were vivid as this passage from an 1887 letter by John Wells suggests:

-

We enter the valley on the southwest, after hours of toil, and feel at once the power of its mingled, yet contrasted, beauty and grandeur. There are, in fact, two valleys, the western -- into which our trail brought us by a sharp descent -- being a mile in length and from an eighth to the half of a mile in width. It was the pasture ground of about twenty mares and their colts, gleaming in the sunlight as if groomed by an hostler every day.

The eastern valley is about two miles long and of ranging width, though nowhere more than half a mile. It was the pasture ground of sheep, and is parted from the western valley by a bold spur of granite from the south, reaching quite to the Tuolumne River. In this spur there is a depression through which a path leads from valley to valley.

Out of these narrow cañons snow waters issue, making up the Tuolumne that waters the valley as a whole. Having done this service, and spread out its beauty to the sun, it passes into a narrow gorge at the west, -- so narrow, indeed, that when the water is high in the spring it is dammed up, and the valley, from end to end, becomes a rock-bound lake. Then, too, a large body of water from the melting snows plunges over the lower rocks on the north, a thousand feet, into the lake below.4

John Muir's impression of the Hetch Hetchy Valley was formed early in his history in the Sierras as he recounts in this passage from a 1908 Sierra Club Bulletin::

- It appears therefore that Hetch-Hetchy Valley, far from being a plain, common, rock-bound meadow, as many who have not seen it seem to suppose, is a grand landscape garden, one of Nature's rarest and most precious mountain mansions. As in Yosemite, the sublime rocks of its walls seem to the nature-lover to glow with life, whether leaning back in repose or standing erect in thoughtful attitudes, giving welcome to storms and calms alike. And how softly these mountain rocks are adorned, and how fine and reassuring the company they keep --their brows in the sky, their feet set in groves and gay emerald meadows, a thousand flowers leaning confidingly against their adamantine bosses, while birds, bees, and butterflies help the river and waterfalls to stir all the air into music -- things frail and fleeting and types of permanence meeting here and blending, as if into this glorious mountain temple Nature had gathered here choicest treasures, whether great or small, to draw her lovers into close confiding communion with her.5

There is indication that in addition to annual visits by sheep and tourists that the valley was surveyed as early as the late 1850s for use as a water source by the Tuolumne Valley Water Company.6 Interest in Hetch Hetchy's potential as a reservoir grew quickly among hydraulic miners in the Sierra foothills, farmers in California's Sacramento Valley and cities in the central part of the state. Interest by the city of San Francisco was first expressed in 1882.

San Francisco's water was supplied primarily by Spring Valley Water, a private company whose investors included some of California's wealthiest bankers and railroad owners. The return on their investment was substantial as was the friction generated between the company and San Francisco city government. Multiple efforts by the city to buy out Spring Valley failed. Pressure on San Francisco to manage its own water system came to a head with the 1906 earthquake and subsequent fire. Damage from the earthquake was substantial, but damage from the fire was catastrophic. Blame was heaped on Spring Valley. In 1901, five years prior to the earthquake, the Roosevelt administration had denied San Francisco's application for a permit to dam Hetch Hetchy. In 1908, despite a new administration and approval from a sympathetic Secretary of Interior, San Francisco's permit was denied by Congress. However, a carefully orchestrated lobbying campaign in 1913 playing on public sympathy resulting from the earthquake and on Progressive political thought that emphasized public ownership of utilities finally won approval for San Francisco to dam the valley.7

1) Dispute over native American use of Hetch Hetchy Valley prior to 1850 is ongoing bewteen Miwok and Paiute natives. Search for both Miwok and Paiute discussions of Hetch Hetchy and describe the argument over the claims of each tribe.

2) Explain what John Muir meant in his comment about sheep in Hetch Hetchy and tourists in Yosemite Valley.

3) Do some research into the impact of the 1906 earthquake on San Francisco's water system and describe the effects on the city.

image from Eadweard Muybridge., "Piute Chief's Lodge," The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley, #1574 available at Calisphere.

1Francis Farquhar , Place Names of the High Sierra (San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1926) as found at the Yosemite Online Library

2Charles Frederick Hoffmann , “Notes on Hetch-Hetchy Valley,” Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences (San Francisco: California, 1868), series 1, 3:5, pp. 368-370 as found at the Yosemite Online Library.

3John Muir, "The Hetch Hetchy Valley," Boston Weekly Transcript, March 25, 1873 as found at the Yosemite Online Library.

4John Wells, "Letter to Charles Stoddard, Summer, 1887," in Charles Stoddard, Beyond the Rockies; a spring journey in California: The Hetch Hetchy Valley (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1894.), pp. 138-140 as found at the Library of Congress American Memory Collection

5John Muir "The Hetch Hetchy Valley," Sierra Club Bulletin, Vol. VI, No. 4, January, 1908 as found at the Yosemite Online Library.

6Carlo M.D. Ferrari, ed., Gold Spring Diary: The Journal of John Jolly (Sonora, California: The Tuolomne County Historical Society, 1966), pp. 70-71 as found at Yosemite Mono Lake Paiute Native American History

7Robert W. Righter, The Battle Over Hetch Hetchy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).