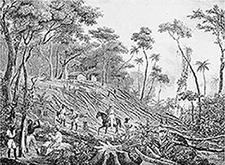

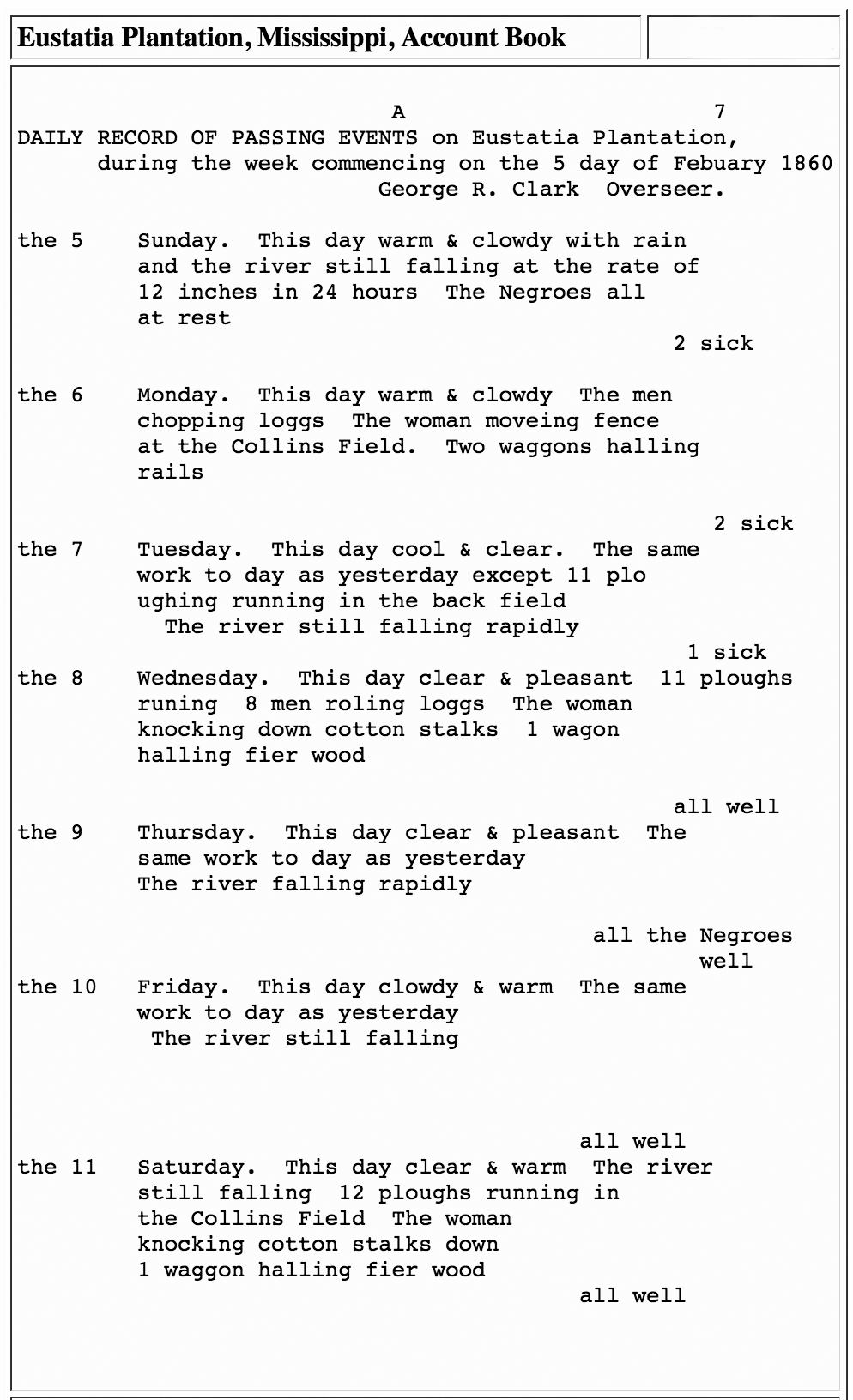

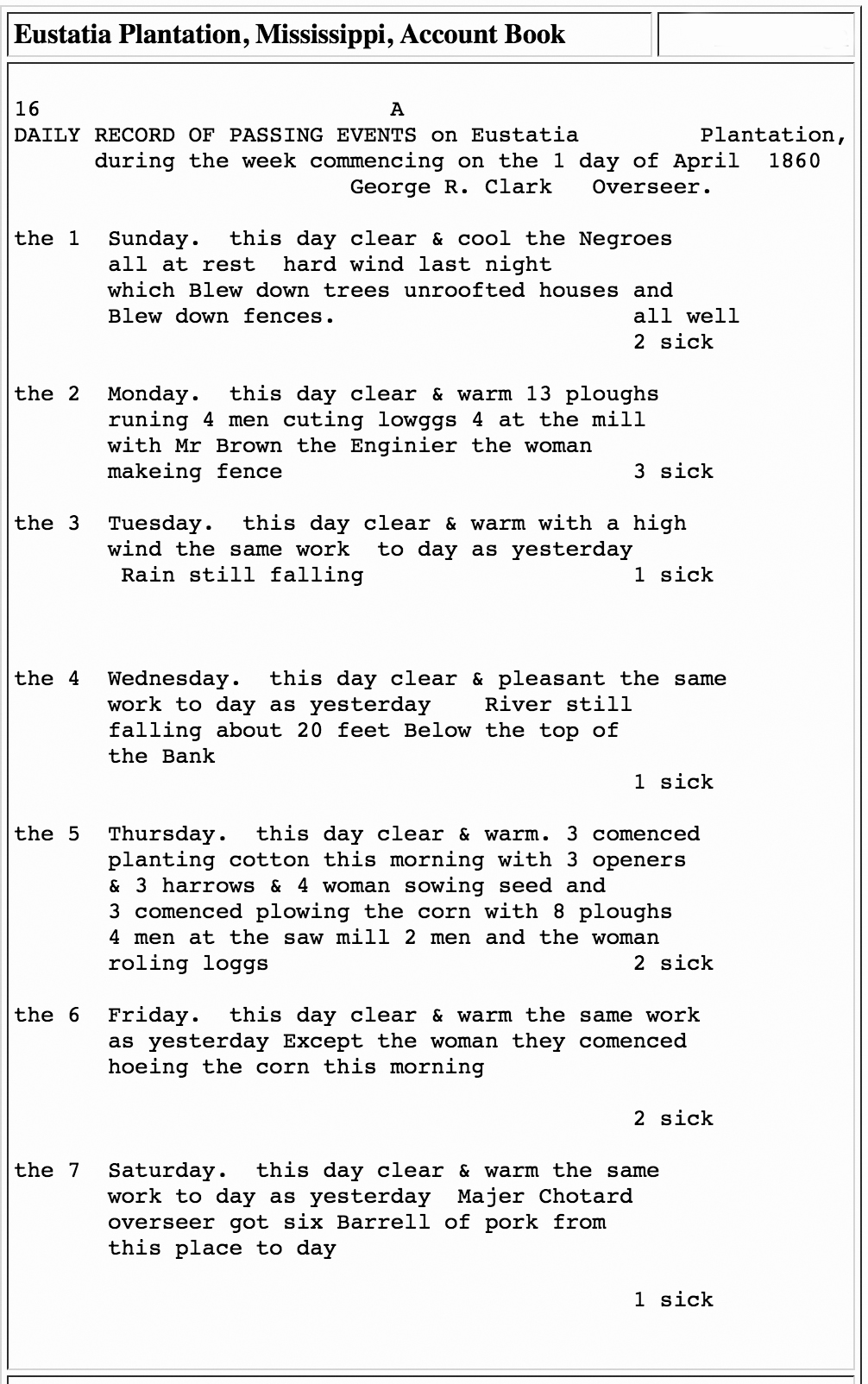

The preparations for planting cotton begin in January; at this time the fields are covered with the dry and standing stalks of the “last year’s crop.” The first care of the planter is to “clean up” for plowing. To do this, the “hands” commence by breaking down the cot- ton stalks with a heavy club, or pulling them up by the roots. These stalks are then gathers ed into piles, and at nightfall set on fire. This labor, together with “housing the corn,” repairing fences and farming implements, consume the time up to the middle of March or the beginning of April, when the plow for the “ next crop” begins its work. First, the “water furrows” are run from five to six feet apart, and made by a heavy plow, drawn either by a team of oxen or mules. This labor, as it will be perceived, makes the surface of the ground in ridges, in.the centre of which is next run a light plow, making what is termed “the drill,” or depository of the seed: a girl follows the light plow, carrying in her apron the cotton seed, which she profusely scatters in the newly-made drill; behind this sewer fol- lows “ the barrow,” and by these various labors the planting is temporarily completed.

From two to three bushels of cotton seed are necessary to plant an acre of ground; the quantity used, however, is but of little consequence, unless the seed is imported, for the annual amount collected at the gin-house is enormous,‘and the surplus, after planting, is either left to rot, to be eaten by the cattle, or scattered upon the fields for manure.

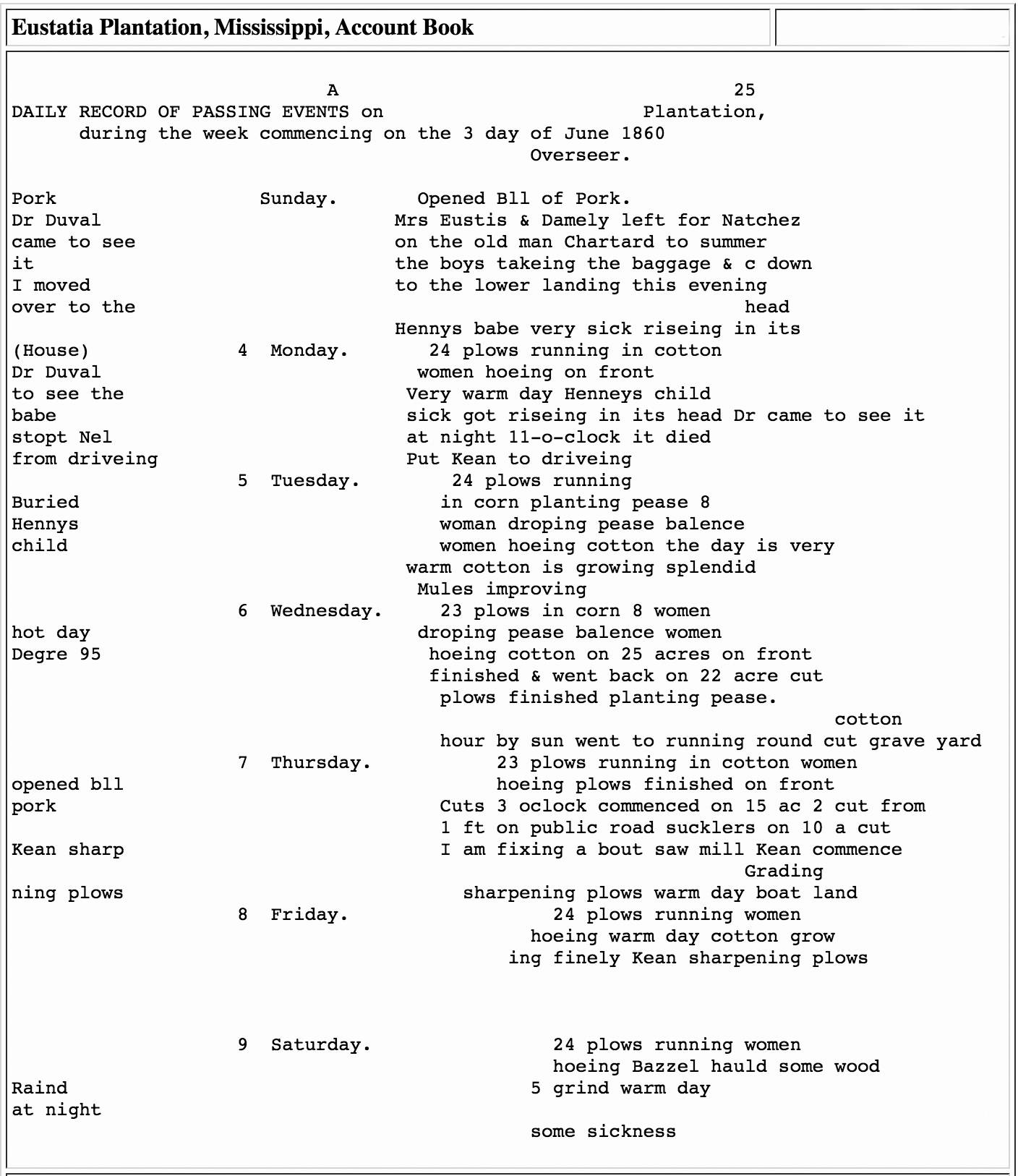

If the weather be favorable, the young plant is discovered making its way through in six or ten days, and "the scraping” of the crop, as it is termed, now begins. A light plow is again called into requisition, which is run along the drill, throwing the earth away from the plant then come the laborers with their hoes, who dexterously cut away the superabundant shoots and the intruding weeds and leave a single cotton-plant in little hills generally two feet apart.

Of all the labors of the field, the dexterity displayed by the negroes in scraping cotton” is most calculated to call forth the admiration of the novice spectator. The hoe is a rude instrument, however well made and handled; the young cotton~plant is as delicate as vegetation can be, and springs up in lines of solid masses, composed of hundreds of plants. The field- hand, however, will single one delicate shoot from the surrounding multitude, and with his rude hoe he will trim away the remainder with all the boldness of touch of a master, leaving the incipient stalk unharmed and alone in its glory; and at nightfall you can look along the extending rows, and find the plants correct in line, and of the required distance of separation from each other.

The planter, who can look over his field in early spring, and find his cotton cleanly scraped”, and his “stand” good, is fortunate; still, the vicissitudes attending the cultivation of the crop have only commenced. Many rows, from the operations of the “ cut-worm,” and from multitudinous causes unknown, have to be replanted, and an unusually late frost may destroy all his labors, and compel him to commence again. But, if no untoward accident occurs, in two weeks after the “scraping, another hoeing takes place, at which time the plow throws the furrow on to the roots of the now strengthening plant, and the increasing heat of the sun also justifying the sinking of the roots deeper in the earth. The pleasant month of May is now drawing to a close, and vegetation of all kinds is struggling for precedence in the fields. Grasses and weeds of every variety, with vines and wild flowers, luxuriate in the newly-turned sod, and seem to be determined to choke out of existence the useful and still delicately grown cotton.

It is a season of unusual industry on the cotton plantations, and woe to the planter who is outstripped in his labors, and finds himself overtaken by the grass. The plow tears up, the surplus vegetation, and 'the hoe tops it off in its luxuriance. The race is a hard one, but industry conquers; and when the third working over of the crop takes place, the cotton plant, so much cherished and favored, begins to overtop its rivals in the fields and begins to cast a chilling shade of superiority over its now intimidated groundlings, and commences to reign supreme.

Through the month of July, the crop is wrought over for the last time; the plant, heretofore of slow growth; now makes rapid advances toward perfection. The plow and hoe are still in

requisition. The water furrows”between the cotton rows are deepened, leaving the cotton growing as it' were. upon a slight ridge; this accomplished, the crop is prepared for the rainy season, should it ensue, and so far advanced, that it is, under any circumstances, beyond the control of art. Nature must now have its sway....

The “cotton bloom, under the matured sun of July, begins to make its appearance. The announcement of the “first blossom” of the neighborhood is a matter of general interest. It is the unfailing sign of the approach of the busy season of fall; it is the evidence that soon the labor of man will, under a kind Providence, receive its reward....

The appearance of a well-cultivated field, if it has escaped the ravages of insects and the destruction of the elements, is of singular beauty. Although it may be a mile in extent, l still it is as carefully wrought as is the mould of the limited garden of the coldest climate. The cotton leaf is of a delicate green, large and luxuriant; the stalk indicates rapid growth, yet it has a healthy and firm look. Viewed from a distance, the perfecting plant has a warm and glowing expression. The size of the cotton plant depends upon the accident of climate and soil. The cotton of Tennessee bears very little resemblance to the luxuriant growth of Alabama and Georgia; but even in those favored states the cotton plant is not every where the same, for in the rich bottom lands it grows to a commanding size, While in the more barren regions it is an humble shrub. In the rich alluvium of the Mississippi the cotton will tower beyond the reach of the tallest picker….

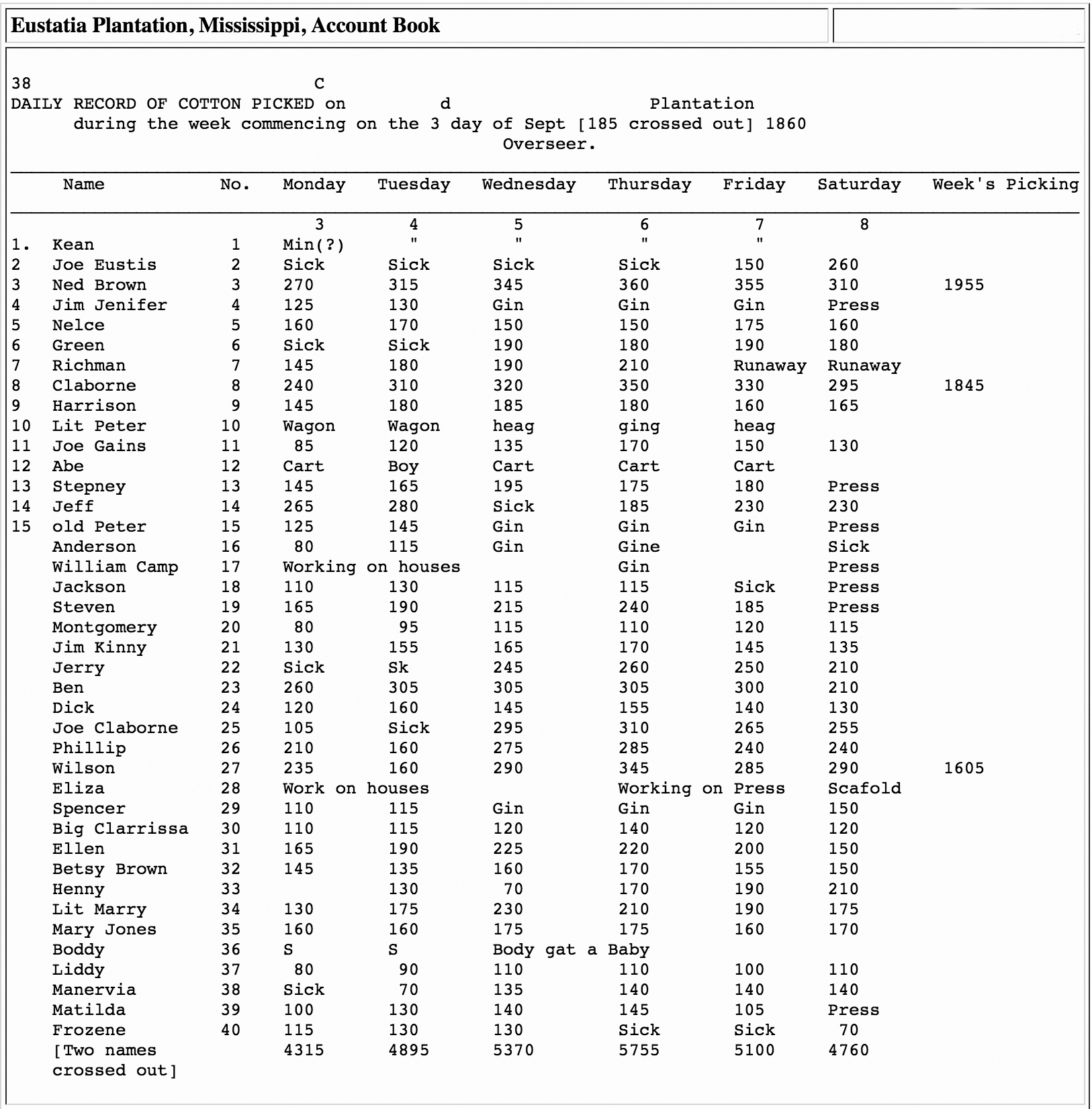

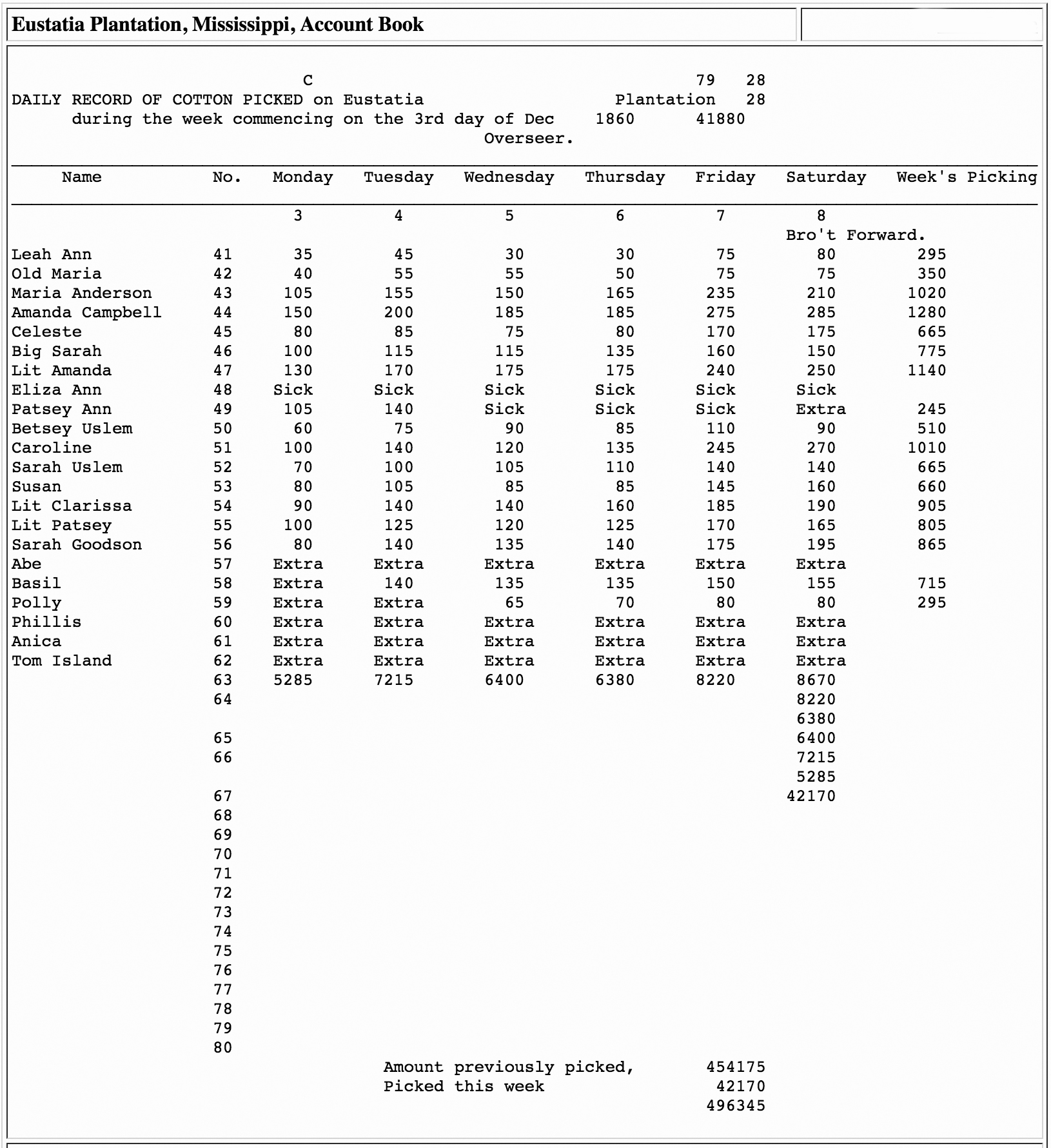

The season of cotton picking commences in the latter part of July, and continues without intermission to the Christmas holidays. The work is not heavy, but becomes tedious from its sameness. The field hands are each supplied with a basket and bag. The basket is left at the head of the cotton-rows;”the bag is suspended from, the picker's neck by a strap, and is used to hold the cotton as it is taken from the boll. When the bag is filled it is emptied into the basket. and this routine is continued through the day. Each hand picks from two hundred and a fifty to three hundred pounds of seed cotton each day, though some negroes of extraordinary ability go beyond this amount.

If the weather be very fine, the cotton is carried from the field direct to the packing house; but generally it is first spread out on scaffolds, where it is left to dry, and picked clean of any “ trash” that may be perceived mixed up with the cotton. Among the most characteristic scenes of plantation life is the returning of the hands at nightfall from the field, with their well filled baskets of cotton upon their heads. Falling unconsciously into line, the stoutest leading the way, they move along in the dim twilight of a winter day with the quietness of spirits rather than human beings

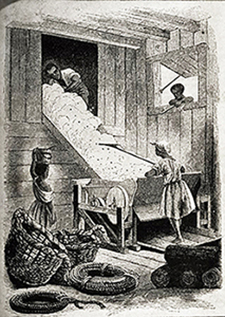

The “packing-room” is the loft of the gin house, and is over the gin-stand. By this arrangement the cotton is conveniently shoved down a causeway into the gin-hopper. We have spoken of the importance of Whitney’s' great invention, and we must now say that much of the comparative value of the staple of cotton depends upon the excellence of the cotton gin. Some separate the staple from the seed far better than others, while all are dependent more or less for their excellence upon the judicious manner they are used. With constant attention, a gin stand, impelled by four mules, will work out four bales of four hundred and fifty pounds each a day; but this is more than the average amount. Upon large plantations the, steam-engine is brought into requisition, which, carrying any number of gins required, will turn out the necessary number of bales per day. Q

The bagging of the cotton ends the labor of its production on the plantation. The power which is used to accomplish this end is generally a single but powerful screw. The ginned cotton is thrown from the packing room down into a reservoir or press, which, being filled, is tramped down by the negroes engaged in the business. When a sufficient quantity has been forced by foot labor into the press, the upper door is shut down, and the screw is applied, worked by horse. By this process the staple becomes almost as solid a mass as stone. By previous arrangement, strong Kentucky bagging has been so placed as to cover the upper and lower side of the pressed cotton. Ropes are now passed round the whole and secured by a knot; a long needle and a piece of twine closes up the openings in the bagging; the screw is then run up, the cotton swells with tremendous power inside of its ribs of ropes the baling is completed, and the cotton is ready for shipment to any part of the world.