Attempts to deal with the famine crisis in Ireland were complex. They

form an intricate web of history, people, ideas, laws, and institutions.

There is no one simple answer to the question of why attempts to deal

with the famine failed - why nearly three million people died or

emigrated during the 1840s and 50s. It was not simply the result of

overpopulation in the face of dependence on a single, failed crop.

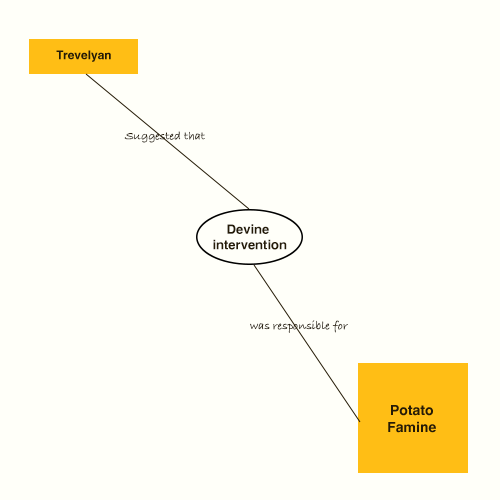

Failure was not the result of an English conspiracy. It was not the

fault of Irish landlords who failed those they held in tenancy. Nor was

it the result of Devine intervention in the form of an old testament God

angered by the sloth and low moral character of the Irish. All of these

answers have been suggested at various times since the 1840s; none of

them alone provide a credible answer. Irish historian Cormac O'Grada has

suggested that the potato blight, the famine that followed, and the

inability to deal with its consequences were the coincidence of :

-

an apocalyptic event in the form of the blight itself,

-

a poor and very large segment of the Irish population - particularly in the West - that was largely dependent on a single crop and that had grown worse off during the course of the previous several decades relative to other parts so of the country,

-

and an English society and political system that had never faced a crisis on this order, was poorly equipped to deal with the scale of the problem, and that ultimately saw the issue as "theirs"; that is, the responsibility of the Irish themselves.1

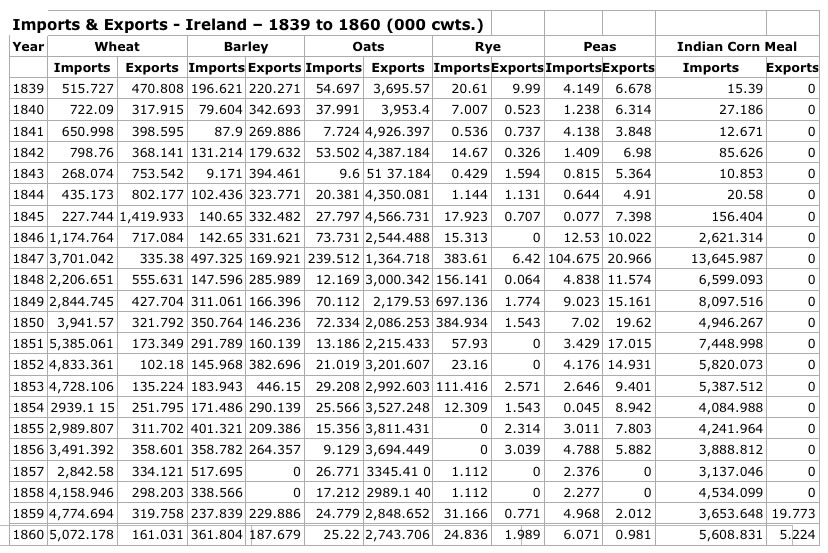

The 1845 failure of the potato crop in Ireland was not the first. Crop failures had occurred several times in the previous 50 years; most recently in 1837. The response of the British government then was establishment of the Poor Law system of relief work to undertake projects such as land reclamation and road construction. This work was administered by Poor Law Unions set up throughout the country and administered locally . In 1845 and 1846 relief work was the first response of the British government under Prime Minister Robert Peel. Unfortunately, widespread abuse of the relief by Irish landowners meant that the work did not always go to those most in need and confidence in the program suffered in Parliament. Peel's correspondence related to Ireland suggests another alternative as well - repeal of the Corn Laws. His hope was to allow additional food stuff, especially corn meal from America, into the Irish market at a price that might be affordable.

The Corn Laws in Great Britain enforced tariffs on grain in order to protect the price of domestic produce for farmers from going too low on the one hand and to prevent prices from rising so high that poor consumers could not afford grain on the other. It had been argued since the laws were first passed in 1815 that stable, higher prices protected from cheaper foreign imports would support higher wages for laborers and, therefore, higher rents, for British landlords. Trade data and arguments for repeal of the laws in 1846, like that of Prime Minister Peel, challenged that line of reasoning. It was argued that:

- The free hand of the market should be allowed to play itself out; that is, the market should operate on the basis of laissez faire economics. This argument was a revolutionary change from the mercantile, protectionist policies of the previous century.

- Evidence in the form of stable wages in the face of increasing prices in the early 1840s contradicted the economic rationale for the Corn Laws.

- Tariffs that prevented millions of starving Irish from buying imported grain could not be tolerated.

The government of Prime Minister Peel wagered its continuation in part on repeal of the Corn Laws and other relief measures. When the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846 it meant that corn could be brought into Irish markets tariff free, sold to local relief committees at cost, and in turn to those most in need, again at cost. However, corn meal was not part of Irish culture in 1847. It was the food of American Indians and slaves, not Irishmen. Its introduction as a substitute for potatoes required not only extreme hunger, but training in its preparation as well.

The effort to repeal the Corn Laws divided Peel's party in Parliament resulting in the opposition leader, Lord Russell, becoming Prime Minister in 1848. Russell was a fierce advocate of the laissez faire economics as was the British Secretary of the Treasury, Charles Trevelyan, who saw the famine as a judgement of God against the "moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the [Irish] people."2 Russell had serious misgivings about extended public welfare projects and their disruption of the free market for both goods and for labor. In the face of evidence of catastrophe in Ireland, though, he reluctantly supported works projects and food relief. Ultimately, though, his government moved to lay responsibility for relief in Ireland onto Irish landowners through modifications in the Irish Poor Laws. This policy change reflected in no small part English popular opinion. Although opinions varied from sympathy to hostility, there was a common sense of burden on English taxpayers and impatience with the never ending effort to deal with Irish problems.

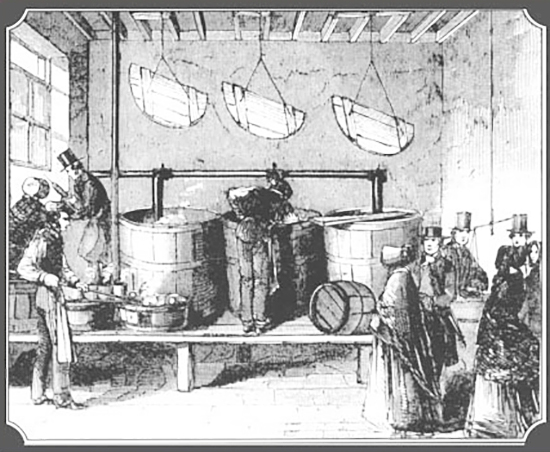

The Poor Laws were an adaptation of the system in England and were instituted for Ireland in 1838 as a means of providing workhouse and medical relief for the truly indigent. The country was divided into 130 Poor Law Unions, each overseen by a local commissioner. Workhouses were built to house and provide work for up to 110,000 of those most in need. The houses were intentionally harsh places to discourage misuse. Expenses were paid in part by the British crown, but in part by a tax on local landowners to encourage local responsibility. The Poor Laws were extended in 1847 as a result of the scope of the famine to provide an increase in the number of workhouses and soup kitchens. Public works projects in the form of road construction and the digging of drainage ditches to promote the expansion of agriculture that had been instituted in the first year of the famine were to be eliminated under the new law. The extension also transferred all responsibility for relief costs to local landowners and landlords. The changes in the law and particularly the "Gregory Clause," forced tenants on as little as a quarter acre to give up their land in order to receive assistance, dramatically changing the incentives for landlords in their relationships with tenants. The motivation for these changes is apparent in passages from the 1847 debate in the English parliament over the Poor Law Extensions. The consequences of these changes were spelled out two years later in the Illustrated London News.

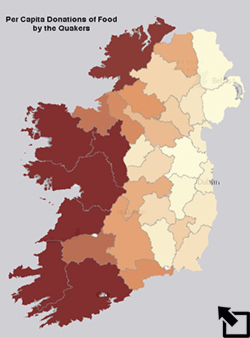

Private relief efforts commenced with the first sign of famine in 1845 - most notably by the Quaker Church in England and the United States. The map at right show shows where the food donations per person were highest. The number of tons of Food is normalized, or divided by, the Population 1841 so that you can see the rate of donations per person in each county. The darker the pattern, the higher the rate. Open the map and you can examine the rates of donation of Money and Seed as well. In addition, many landlords provided rent relief and some supported emigration with grants to tenants and their families to move abroad. Efforts such as these, however, paled in comparison to the scale of the famine.

1) Your job is to piece together a picture of efforts to relieve the

famine based on the first hand accounts and data linked in the

narrative above. Your picture will take the form of a Famine Concept Map outlining the history of famine

relief efforts. Click on the link and follow the instructions at the

bottom of the page.

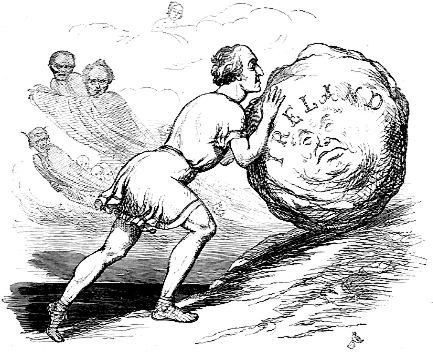

2) Political cartoons and drawings have been and continue to be an

important source of editorial content in newspapers and other

periodicals. Create a drawing or cartoon of your own that focuses on

one aspect of the famine relief efforts. Write a short summary

explaining the point of your work and how it relates to ideas in your

concept map.

1Cormac O'Grada, "Ireland's

Great Famine," ReFresh, (15)

Autumn, 1992 and Cormac O'Grada, "Ireland’s

Great Famine :An Overview,"

University College Dublin; Centre for Economic Research, 2011.

2Sir Charles Trevelyan, Writings & Studies. The

Irish crisis, being a narrative of the measures for the relief of

the distress caused by the Great Irish Famine of 1846–7. London:

1880, downloaded May 20, 2015.

Last modified in April, 2024 by Rick Thomas

The English Labourer

The English Labourer

The Modern Sisyphus

The Modern Sisyphus