Understanding the Cherokee removal requires that you develop a sense of Cherokee culture. You are going to examine a variety of materials related to Cherokee life in the late 1700s and early 1800s. These include written accounts, Cherokee legend, archeological artifacts, as well as photographs and paintings of historical reconstructions. You will find that there is no one clear picture of who these people were. It will be your job to piece together the bits of evidence you have to study and mentally create your own Cherokee portrait.

The list below includes a variety of materials related to the Cherokee. Make copies of the note sheet that you can use with each of the sources that you or your group has been assigned. As you study each document follow the example given below and take notes about the bits and pieces of Cherokee culture suggested by the details of each source. The materials represent characterizations of the Cherokee over a period of about 50 years so pay close attention to the date. Change happens.

A Sketch of the Cherokee & Choctow Indians

Condition of the Cherokee People

The Coming of Corn - Cherokee Legend

Agriculture among the early 19th century Cherokee was often seen as an indication that they were adapting to European culture. However, corn was a fundamental part of Cherokee life as this story attests.

Long ago, when the world was new, an old woman lived with her grandson in the shadow of the big mountain. They lived happily together until the boy was seven years old. Then his Grandmother gave him his first bow and arrow. He went out to hunt for game and brought back a small bird.

"AH," said the Grandmother, "You are going to be a great hunter. We must have a feast." She went out to the small storehouse behind their cabin. She came back with dried corn in her basket and made a fine tasting soup with the bird and the corn. From that point on the boy hunted. Each day he brought back something and each day the Grandmother took some corn from the storage house to make soup. One day though, the boy peeked into the storehouse. It was empty! But that evening, when he returned with game to cook, she went out again and brought back a basket filled with dry corn.

"This is strange," the boy said to himself. "I must find out what is happening."

The next day, when he brought back his game, he waited until his Grandmother had gone out for her basket of corn, and followed her. He watched her go into the storehouse with the empty basket. He looked through a crack between the logs and saw a very strange thing. The storehouse was empty, but his Grandmother was leaning over the basket. She rubbed her hands along the sides of her body, and dried corn poured out to fill the basket. Now the boy grew afraid. Perhaps she was a witch! He crept back to the house to wait. When his Grandmother returned, though, she saw the look on his face.

"Grandson," she said, "you followed me to the shed and saw what I did there."

"Yes, Grandmother," the boy answered.

The old woman shook her head sadly. "Grandson," she said, 'then I must get ready to leave you. Now you know my secret I can no longer live with you as I did before. Before the sun rises tomorrow I shall be dead. You must do as I tell you, and you will be able to feed yourself and the people when I have gone."

The old woman looked very weary and the boy started to move towards her, but she motioned him away. "You cannot help now, Grandson. Simply do as I tell you. When I have died, clear away a patch of ground on the south side of our lodge, that place where the sun shines longest and brightest. The earth there must be made completely bare. Drag my body over that ground seven times and then bury me in that earth. Keep the ground clear. If you do as I say, you shall see me again and you will be able to feed the people."

Then the old woman grew silent and closed her eyes. Before the morning came, she was dead.

Her grandson did as he was told. He cleared away the space at the south side of the cabin. It was hard work, for there were trees and tangled vines, but at last the earth was bare. He dragged his Grandmother's body, and wherever a drop of her blood fell, a small plant grew up. He kept the ground clear around the small plants, and as they grew taller it seemed he could hear his Grandmother's voice whispering in the leaves. Time passed and the plants grew very tall, as tall as a person, and the long tassels at the top of each plant reminded the boy of his Grandmother's long hair. At last, ears of corn formed on each plant and his Grandmother's promise had come true. Now, though she had gone from the earth as she had once been, she would be with the people forever as the corn plant, to feed them.

from "The Coming of Corn." as found at Mythologies.

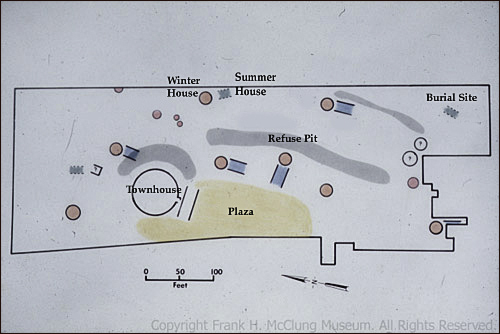

the mid-18th century Cherokee village of Chota

The map shows the extent of the site of the 18th century Cherokee village of Chota along the Little Tennessee River as well as the dwellings that were discovered there.

Gerald F. Schroed, Drawing of the mid-18th century Cherokee village of Chota, in the Southeastern Native American Documents Collection, 1730-1842, part of the GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

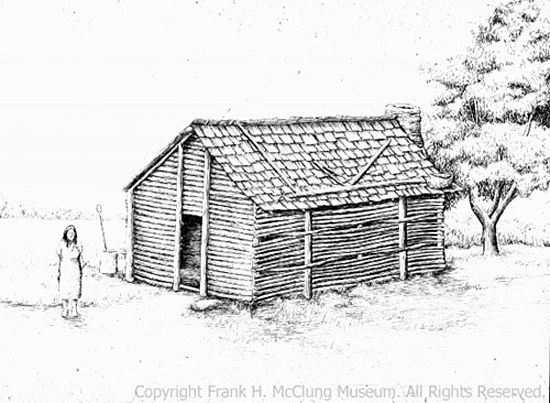

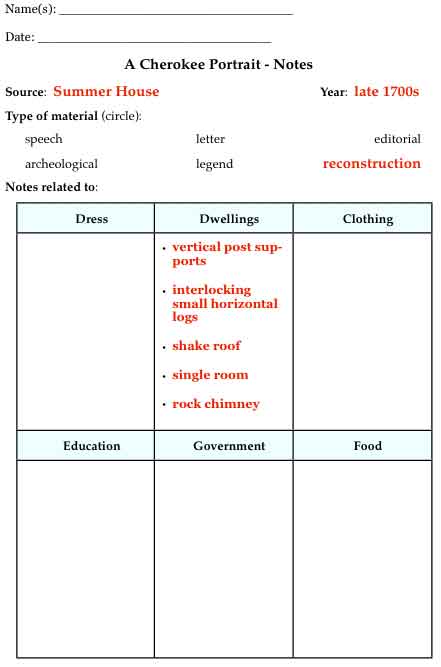

Drawing depicting a late 18th century Cherokee domestic structure

Thomas Whyte, Drawing depicting a late 18th century Cherokee domestic structure, in the Southeastern Native American Documents Collection, 1730-1842, part of the GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

photograph of Charred Corn Cobs, 18th Century Cherokee Village of Tanassee

This photo shows a pit of charred corn cobs in the 18th century Cherokee village of Tanasee. They were used to smudge ceramic pots and process deer hides.

J. Worth Greene,Photograph of small pit filled with charred corn cobs, 18th century Cherokee Village of Tanassee, in the Southeastern Native American Documents Collection, 1730-1842, part of the GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

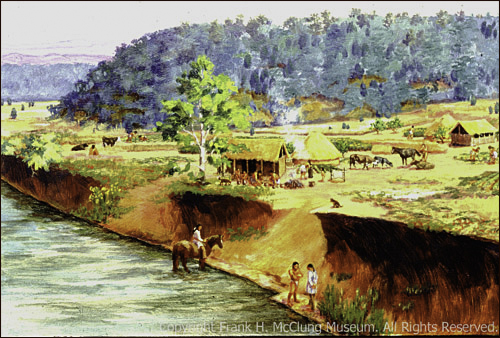

painting depicting A Cherokee Farmstead in the mid-18th Century

This painting is an artist's rendition of what University of Tennessee archeologists discovered in their dig at the site of the 18th century Cherokee village of Chota along the Little Tennessee River.

Painting depicting a Cherokee farmstead in the mid-18th century, in the Southeastern Native American Documents Collection, 1730-1842, part of the GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia. GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

A Sketch of the Cherokee and Choctaw Indians

In 1819 approximately one third of the Cherokee population was removed west of the Mississippi River into Arkansas following a treaty that resulted in Cherokee land in Tennessee and Alabama being ceded to the United States. Captian Stuart was sent to report on the condition of the Cherokee in their new home.

The Cherokees are settled all along the Arkansas and Canadian rivers, from the State of Arkansas to the Iine of the Creek nation. They are also on both sides of the Neosho for some distance up it, and particularly on its eastern branches, where they have a delightful and fertile country. Their settlements do not extend much on the west side of the. Neosho. They are thickly settled the Illinois and all its tributaries; and also upon, all the other small streams running through the country. Springs of water are scarce all over this country; but the clear running and shaded bayous form an excellent substitute. Good water is easily procured by sinking wells, which arc becoming very common in the country. The Cherokees form their buildings precisely like those of the frontier settlements of the United States. Their land is cleared and cultivated in the same manner, and their fences, stables, &c., are all made after the fashion of the whites. Their houses are, for the most part, cabins, covered with boards or shingles four feet long, and arc confined by weightless. Some of them are built of hewn logs; others are framed and weather boarded, and have good shingled roofs, plank floors, and, in many cases, have good stone chimneys. Many of the Cherokees own slaves, whom they treat with great kindness and humanity. Some few of those residing cast of the Mississippi, own from fifty to one hundred negroes. They have entirely abandoned the chase, except amusement, and live entirely by cultivating the earth, and raising stock; and they may be termed agricultural or pastoral people. They raise corn principally for bread stuff; and for feeding stock which is kept in constant service, such as horses, &c. They raise some for home market. They raise immense herds of cattle, hors&, bogs, with some sheep, and all kinds of poultry in abundance. They have not any extensive market for their poultry; but are able to make sale of large quantities of beef cattle, hogs, &c. At present they arc very deficient in the way of mills, there not being more than two or three mills in the whole nation. They are obliged, therefore, to use the steel-mill, or to pound their corn into hominy or meal, of which they make a considerable portion of their diet. Their provisions are usually served up on tables, much in the mariner of the whites. But many of them have a preparation of corn, made in a manner peculiar to all the Indian tribes of the south, and which has been brought on by them from their earliest use of corn, The corn, previous to being boiled, is soaked, or steeped in lye, which imparts to it when cooked a kind of alkaline taste. This preparation is used mostly by the old or less civilized portion of the people. It is called by the Cherokee, caynohana. A similar preparation used by the Creeks, is called safka; and, by the Choctaws, tomfullah. The whole of the Cherokees use much sugar and coffee; and many of them live precisely as the Americans do. They are not well acquainted with the manner of curing bacon, but are improving in that art. Some of them make excellent butter, not only in sufficient quantities for their own use, but also for market.

The women of the Cherokee nation are no longer made to perform the entire labor of the family, as was the case with them in their less civilized state, mind which is even now the case with the barbarous tribes. Their duties are generally confined In the house; they spin, weave, knit, sew, cook, &c., and do all manner of housework common for women to do in all civilized communities. The Cherokee females all use the side-saddle when riding; but formerly their position on horseback was different.

Dress and Manner

The Cherokees at present wear but very little of their native dress. Some of the old ‘men continue to wear leggins and moccasins made of dressed buckskin, and a flap made of cloth which is worn under is white shirt of the usual fashion of the whites, which is worn loose. They also wear a hunting-shirt or toga, made of domestic cotton or calico. They wear a turban, which is constructed by rolling or winding a large handkerchief or shawl into a circular form so as to fit and rest upon the upper side of the head, in such a manner as to leave bare the top and lower back part of the head. It is put on and taken off the head with as much ease as a hat would he, and retains its shape without trouble to the owner. The younger men dress after the fashion of the whites except that some of them seem to prefer the turban and the toga to the hat and coat, and generally wear them; while others of them dress exactly as the whites do. Some of that number wear as fine cloth and other materials as the most fashionable of the whites. The women all dress more or less after the manner of the white women. The older women usually wear a plain domestic or calico gown, and tie up their hair with a string in place of using a comb for the purpose of keeping it up, as is usual with the younger ones. The younger females dress precisely as the women of the United States do; and according to their wealth and ability follow them closely through all the European fashions in form and materials, except that they seldom wear a bonnet, but in lieu thereof after placing their hair up in a most fanciful manner with fine large and side combs, they place over their heads a fine silk handkerchief in a very tasteful manner so as to appear quite ornamental. This handkerchief is sometimes so very fine, and so light a texture, as to show their hair and combs through it.

from Capt. John Stuart, A Sketch of the Cherokee and Choctaw Indians, Little Rock: Woodruff and Pew, 1831, pp 12-13.

New Echota Cabin

The town of New Echota became the Cherokee capital in 1825 and remained so until 1835 when divisions within the tribe and Georgia laws forced leaders to move the capital to Red Clay, Tennessee. The cabin below is a reconstructed version of those built in New Echota in the late 1820s.

photo courtesy of The Georgia Department of Natural Resources, New Echota Historic Site

from An Address to the Whites by Elias Boudinot

Educated in the north, Boudinot's principle claim to fame was as editor of the Cherokee Phoenix. He was forced to resign from this position, though, in 1832 because of his change in opinion regarding Cherokee removal to the west. He was one of a small group of Cherokee, including Major Ridge, who eventually negotiated and signed the Treaty of New Echota resulting in the Trail of Tears. At the time of this speech Boudinot was a leading proponent of Cherokee assimilation into American culture as a means of preserving the tribe's place in the eastern United States.

To those who are unacquainted with the manners, habits and improvements of the aborigines of this country, the term Indian is pregnant with ideas the most repelling and degrading. But such impressions, originating as they frequently do, from infant prejudices although they hold too true when applied to some, do great injustice to many of this race of beings.

Some there are, perhaps even in this enlightened assembly, who at the bare sight of an Indian, or at the mention of the name, would throw back their imaginations to ancient times, to the savages of savage warfare, to the yells pronounced over the mangled bodies of women and children, thus creating an opinion, inapplicable and highly injurious to those for whose temporal interest and eternal welfare, I come to plead.

What is an Indian? Is he not formed of the same materials with yourself? For "Of one blood God created all the nations that dwell on the face of the earth." Though it be true that he is ignorant, that he is a heathen, that he is a savage; yet he is no more than all others have been under similar circumstances. Eighteen centuries ago what were the inhabitants of Great Britain?

You here behold an Indian, my kindred are Indians, and my fathers sleeping in the wilderness grave--they too were Indians.

But I am not as my fathers were--broader means and nobler influences have fallen upon me. Yet I was not born as thousands are, in a stately dome and amid the congratulations of the great, for on a little hill, in a lonely cabin, overspread by the forest oak I first drew my breath; and in a language unknown to learned and polished nations, I learnt to lisp my fond mother's name. In after days, I have had greater advantages than most of my race; and I now stand before you delegated by my native country to seek her interest, to labour for her respectability, and by my public efforts to assist in raising her to an equal standing with other nations of the earth....

The Cherokee nation lies within the charted limits of the states of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama. Its extent as defined by treaties is about 200 miles in length from East to West, and about 120 in breadth. This country which is supposed to contain about 10,000,000 of acres exhibits great varieties of surface, the most part being hilly and mountainous, affording soil of no value. The vallies [valleys] however, are well watered and afford excellent land, in many parts particularly on the large streams, that of the first quality. The climate is temperate and healthy, indeed I would not be guilty of exaggeration were I to say, that the advantages which this country possesses to render it salubrious, are many and superior. Those lofty and barren mountains, defying the labour and ingenuity of man, and supposed by some as placed there only to exhibit omnipotence , contribute to the healthiness and beauty of the surrounding plains, and give us to that free air and pure water which distinguish our country. These advantages, calculated to make the inhabitants healthy, vigorous, and intelligent, cannot fail to cause this country to become interesting. And there can be no doubt that the Cherokee Nation however obscure and trifling it may now appear, will finally become, if not under its present occupants, one of the Garden spots of America. And here, let me be indulged in the fond wish, that she may thus become under those who now possess her; and ever be fostered, regulated and protected by the generous government of the United States.

The population of the Cherokee Nation increased for the year 1810 to that of 1824, 2000 exclusive of those who emigrated in 1818 and 19 to the west of the Mississippi--of those who reside on the Arkansas the number is supposed to be about 5000.

The rise of these people in their movement toward civilization, may be traced as far back as the relinquishment of their towns; when game became incompetent to their support, by reason of the surrounding white population. They then betook themselves to the woods commenced the opening of small clearings, and the raising of stock; still however following the chase. Game has since become so scarce that little dependence for subistence [subsistence] can be placed upon it. They have gradually and I could almost say universally forsaken their ancient employment. In fact, there is not a single family in the nation, that can be said to subsist on the slender support which the wilderness would afford. The love and the practice of hunting are not now carried to a higher degree, than among all frontier people whether white or red. It cannot be doubted, however, that there are many who have commenced a life of agricultural labor from mere necessity, and if they could, would gladly resume their former course of living. But these are individual failings and ought to be passed over.

On the other hand it cannot be doubted that the nation is improving, rapidly improving in all those particulars which must finally constitute the inhabitants an industrious and intelligent people.

It is a matter of surprise to me, and must be to all those who are properly acquainted with the condition of the Aborigines of this country, that the Cherokees have advanced so far and so rapidly in civilization. But there are yet powerful obstacles, both within and without, to be surmounted in the march of improvement. The prejudices in regard to them in the general community are strong and lasting...

In 1810 There were 19,500 cattle; 6,100 horses; 19,600 swine 1,037 sheep; 467 looms; 1600 spinning wheels; 30 wagons; 500 ploughs; 3 saw-mills; 13 grist-mills &c. At this time there are 22,000 cattle; 7,600 Horses; 46,000 swine; 2,500 sheep; 762 looms; 2488 spinning wheels; 172 wagons; 2,943 ploughs [plows]; 10 saw-mills; 31 grist-mills; 62 Blacksmith-shops; 8 cotton machines; 18 schools; 18 ferries; and a number of public roads. In one district there were, last winter, upwards of 1000 volumes of good books; and 11 different periodical papers both religious and political, which were taken and read. On the public roads there are many decent Inns, and few houses for convenience, &c. [et cetera], would disgrace any country. Most of the schools are under the care and tuition of christian missionaries, of different denominations, who have been of great service to the nation, by inculcating moral and religious principles into the minds of the rising generation. In many places the word of God is regularly preached and explained, both by missionaries and natives; and there are numbers who have publicly professed their belief in the merits of the great Savior of the world. It is worthy of remark, that in no ignorant country have the missionaries undergone less trouble and difficulty, in spreading a knowledge of the Bible than in this. Here, they have been welcomed and encouraged by the proper authorities of the nation, their persons have been protected, and in very few instances have some individual vagabonds threatened violence to them. Indeed it may be said with truth, that among no heathen people has the faithful minister of God experienced greater success, greater reward for his labour, than in this...

There are three things of late occurrence, which must certainly place the Cherokee Nation in a fair light, and act as powerful argument in favor of Indian improvement.

First. The invention of letters.

Second. The translation of the New Testament into Cherokee.

And third. The organization of a Government.

...There are, with regard to the Cherokees and other tribes, two alternatives; they must either become civilized and happy, or sharing the fate of many kindred nations, become extinct. If the General Government continue its protection, and the American people assist them in their humble efforts, they will, they must rise. Yes, under such protection, and with such assistance, the Indian must rise like the Phoenix, after having wallowed for ages in ignorant barbarity. But should this Government withdraw its care, and the American people their aid, then, to use the words of a writer, "They will go the way that so many tribes have gone before them; for the hordes that still linger about the shores of Huron, and the tributary streams of the Mississippi, will share the fate of those tribes that once lorded it along the proud banks of the Hudson; of that gigantic race that said to have existed on the borders of the Susquehanna; of those various nations that flourished about the Potomac and the Rhappahannoc, and that peopled the forests of the vast valley of Shenandoah. They will vanish like a vapour from the face of the earth their very history will be lost in forgetfulness, and the places that now know them will know them no more." There is, in Indian history, something very meloncholy, and which seems to establish a mournful precedent for the future events of the few sons of the forest, now scattered over this vast continent. We have seen every where the poor aborigines melt away before the white population. I merely speak of the fact, without at all referring to the cause. We have seen, I say, one family after another, one tribe after another, nation after nation pass away; until only a few solitary creatures are left to tell the sad story of extinction.

Shall this precedent be followed? I ask you, shall red men live, or shall they be swept from the earth? With you and this public at large, the decision chiefly rests. Must they perish? Must they all, like the unfortunate Creeks, (victims of the unchristian policy of certain persons,) go down in sorrow to their graves.

They hang upon your mercy as to a garment. Will you push them from you, or will you save them? Let humanity answer.

from Elias Boudinot, "An address to the whites delivered in the First Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, on the 26th of May, 1826," in the GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

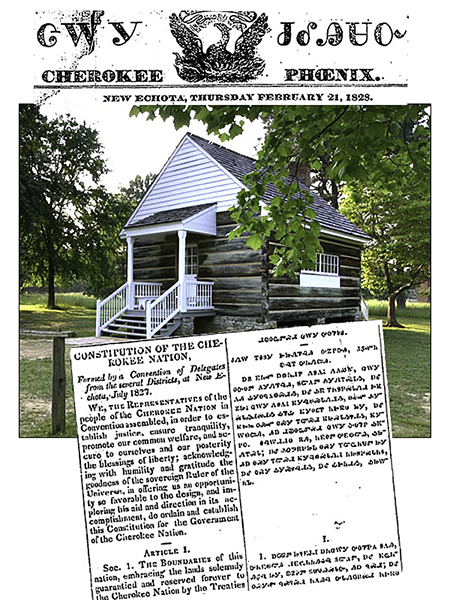

Home of the Cherokee Phoenix

New Echota was the home of the Cherokee legislature and the Cherokee Phoenix, the nation's newspaper. As you can see in the article excerpted below, the news was often presented in both English and Cherokee using the alphabet devised by Sequoya.

photo courtesy of The Georgia Department of Natural Resources, New Echota Historic Site Excerpts from the Cherokee Phoenix, February 21, 1828 v1 n1 from Georgia Historic Newspapers, part of the GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

A letter on the Condition of the Cherokee People

Samuel Worchester was a Methodist missionary living among the Cherokee in New Echota. His arrest and trial under contested Georgia laws claiming jurisdiction over Cherokee territory led to the U. S. Supreme Court decision in the case of Worchester v. State of Georgia in which the court ruled against Georgia's claim; a decision that President Jackson refused to enforce.

New Echota, Cher. Nation

March 15, 1830

Mr. Wm. S. Coodey

Washington City.

Dear Sir:

I cheerfully comply with your request, that I would forward to you a statement respecting the progress of improvement among your people, the Cherokees.

... It may not be amiss to state, briefly, what opportunities I have enjoyed of forming a judgment respecting the state of the Cherokee people. It was four years last October, since I came into the nation, during which time I have made it my home, having resided two years at Brainerd, and the remainder of the time at this place. Though I have not spent very much of the time in travelling, yet I have visited almost every part of the nation, except a section on the Northeast. Two annual sessions of the General Council have passed while I have been residing at the Seat of Government, at which times a great number of the people of all classes and from all parts are to be seen.

... The printed constitution and laws of your nation, also, you doubtless have. They show your progress in civil polity. As far as my knowledge extends, they are executed with a good degree of efficiency, and their execution meets with not the least hinderance from anything like a spirit of insubordination among the people. Oaths are constantly administered in the courts of justice, and I believe I have never heard of an instance of perjury.

It has been well observed by others, that the progress of a people in civilizations is to be determined by comparing the present with the past. I can only compare what I see with what I am told has been.

The principal chief is about forty years of age. When he was a boy, his father procured him a good suit of clothes, in the fashion of the sons of civilized people; but he was so ridiculed by his mates as a white boy that he took off his new suit, and refused to wear it. The editor of the Cherokee Phoenix is twenty-seven years old. He well remembers that he felt awkward and ashamed of his singularity, when he began to wear the dress of a white boy. Now every boy is proud of a civilized suit, and those feel awkward and ashamed of their singularity who are destitute of it. At the last session of the General Council, I scarcely recollect having seen any members who were not clothed in the same manner as the white inhabitants of the neighboring States; and these very few, (I am informed that the precise number was four) who were partially clothed in Indian style, were, nevertheless, very decently attired. The dress of civilized people is general throughout the nation. I have seen, I believe, only one Cherokee woman, and she an aged woman, away from her home, who was not clothed in at least a decent long gown. At home only one, a very aged woman, who appeared willing to be seen in original native dress; three or four, only, who had at their own houses dressed themselves in Indian style, but hid themselves with shame at the approach of a stranger. I am thus particular, because particularity gives more accurate ideas than general statements. Among the elderly men there is yet a considerable portion, I dare not say whether a majority or a minority, who retain the Indian dress in part. The younger men almost all dress like the whites around them, except that the greater number wear a turban instead of a hat, and in cold weather a blanket frequently serves for a cloak. Cloaks, however, are becoming common. There yet remains room for improvement in dress, but that improvement is making with surprising rapidity.

The arts of spinning and weaving, the Cherokee women generally, put in practice. Most of their garments are of their own spinning and weaving, from cotton the produce of their own fields; though considerable northern domestic, and much calico, is worn, nor is silk uncommon. Numbers of the men wear imported cloths, broadcloths (sic), &c. and many wear mixed cotton and wool, the manufacture of their wives; but the greater part are clothed principally in cotton.

Except in the arts of spinning and weaving, but little progress has been made in manufactures. A few Cherokees, however are mechanics.

Agriculture is the principal employment and support of the people. It is the dependence of almost every family. As to the wandering part of the people, who live by the chase, if they are to be found in the nation, I certainly have not found them, nor even heard of them, except from the floor of Congress, and other distant sources of information. I do not know of a single family who depend, in any considerable degree, on game for support. It is true that deer and turkies (sic) are frequently killed, but not in sufficient numbers to form any dependence as the means of subsistence. The land is cultivated with very different degrees of industry; but I believe that few fail of an adequate supply of food. The ground is uniformly cultivated by means of the plough, and not as formerly, by the hoe only.

The houses of the Cherokees are of all sorts; from an elegant painted or brick mansion, down to a very mean log cabin. If we speak, however, of the mass of the people, they live in comfortable log houses, generally one story high, but frequently two; sometimes of hewn logs, and sometimes unhewn; commonly with a wooden chimney, and a floor of puncheons, or what a New England man would call slabs. Their houses are not generally well furnished, many have scarcely any furniture, though a few are furnished even elegantly, and many decently. Improvement in the furniture of their houses appears to follow after improvement in dress, but at present is making rapid progress.

As to education, the number who can read and write English is considerable, though it bears but a moderate proportion to the whole population. Among such, the degree of improvement and intelligence is various. The Cherokee language, as far as I can judge, is read and written by a large majority of those between childhood and middle age. Only a few who are much beyond middle age have learned.

In regard to the progress of religion, I cannot, I suppose, do better than to state, as nearly as I am able, the number of members in the churches of the several denominations. The whole number of native members of the Presbyterian churches is not far from 180. In the churches of the United Brethren are about 54. In the Baptist churches I do not know the number; probably as many as 50. The Methodists, I believe reckon in society, more than 800; of whom I suppose the greater part are natives. Many of the heathenish customs of the people have gone entirely, or almost entirely, into disuse, and others are fast following their steps. I believe the greater part of the people acknowledge the Christian religion to be the true religion, although many who make this acknowledgment know very little of that religion, and many others do no feel its power. Through the blessing of our God, however, religion is steadily, gaining ground.

But, it will be asked, is the improvement which has been described, general among the people, and are the full-blooded Indians civilized, or only the half-breeds? I answer that, in the description which I have given, I have spoken of the mass of the people, with out distinction. If it be asked however, what class are most advanced- I answer, as a general thing- those of mixed blood. They have taken the lead, although some of full blood are as refined as any. But, though those of mixed blood are generally in the van, as might naturally be expected, yet the whole mass of the people is on the march....

Your sincere friend,

SAMUEL A. WORCESTER.

from Samuel A. Worchester, "Letter on the Condition of the Cherokee People," in the Cherokee Phoenix," v3 n3 Saturday, May 8, 1830 .

Interior View of the Home of Major Ridge

As the photo below suggests the Ridge family was among the wealthiest among the Cherokee. Ridge was one of the principle leaders of the tribe and during his life pushed the process of "civilizing" the tribe - accommodating to European culture and government. He eventually led a small group of leaders in negotiating and signing the Treaty of New Echota ceding all remaining Cherokee land in the east in the belief that there could be no other alternative to encroachment on Cherokee land but the losing proposition of war with the United States.

photo from The Chieftains Museum on The Chieftains Trail web page.

Editorial in the Philidelphian, May 8, 1830

Not all of the nation's religious leaders were sympathetic to the Cherokee cause. Ely's editorial appeared in the Philadelphian, a conservative Presbyterian paper, and was reprinted in the Cherokee Phoenix provoking a number of responses.

The present miserable condition of the majority of the Indians resident on this side of the Mississippi calls loudly for such a measure [removal]; for altho' the gospel has greatly benefitted all who have been brought under its benign influences, still the civilized Indians are generally of mixed blood. being one half or one quarter white; and the mass of the people, even among the Cherokees, are idle, uncultivated, and destitute of most of the comforts of life. At this moment they are more than half naked, and frequently half starved. I have it only second hand (and through one of the most honorable and upright senators of the United States), from a leading man of the nation of Cherokees, who is himself rich, and has reared a numerous family by a Cherokee wife. that the Indians frequently came fifty and sixty miles over the mountains. to his grist mill to beg a peck of Indian meal....

There certainly exist erroneous apprehensions concerning the extent to which improvement has advanced among them. Religious people and missions, however, are not to be blamed because they have not rescued all from vagrancy and want. It is well that they have accomplished so much; and are striving to do more.

Those Indians, generally half-Indians, who have built their houses and cultivated lands by their slaves, consider with propriety, that their dwellings and corn-fields, and tobacco plantations are not to be the common property of the wanderers of their nation. The seclusion of these cultivated spots, so far as they can be appropriated to the exclusive profit of those who have made the improvements upon them, are at present, however, detrimental to those natives who still depend on game and the chase; and in this way the civilization of a part of the people has rendered the condition of those who remain uncivilized more miserable.

In some instances those who would have cultivated a farm have been deterred by knowing, that every hungry Indian brother considers the whole Cherokee reservation a common, and will carry off the fruits of the labours of his neighbor, whenever he can find, and thinks that he needs them.

from Ezra Stiles Ely, The Philadelphian and the Indians, reprinted in , v2 n47 March 10, 1830 from Georgia Historic Newspapers,

Portrait Note Sheet

1) Share your notes and understanding of the material with others who have studied the rest of the documents. Make sure that you discuss any contradictions that you discover and how you resolve them. Do you find any of the sources unbelievable? Why?

2) Write a one page summary in which you characterize the Cherokee in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Discuss changes that occurred over time.