The argument over Cherokee removal was national in scope and involved questions of states' rights and the limits of federal control that went far beyond concerns about the Cherokee people. The role of northern churches in arguing the Cherokee case foreshadowed their involvement in the question of slavery in the 1840s and 50s. The debate extended from the President of the U.S. to the Supreme Court to Congress to the legislatures of the states involved and into the press both nationally and locally. The activity below is designed to allow you to sort through the various arguments for Cherokee removal and to weigh the merits of the debate on both sides.

Use copies of the Removal Debate worksheet to help you organize your thoughts as you study the arguments and evidence both for and against moving the Cherokees west of the Mississippi.

| 1829 | Georgia Journal newspaper notice |

Jeremiah Evarts Report on Indian Relations |

Frontier Neighbors Cherokee Phoenix |

|

| 1830 | Report from the House Committee on Indian Affairs |

Edward Everett Speech before US House of Representatives |

William Wirt Letter |

Indian Removal Act U.S. Congress |

| 1831 | ||||

| 1832 | Land Grant State of Georgia |

|||

| 1833 | John Ridge Cherokee Leader |

|||

| 1834 | ||||

| 1835 | Andrew Jackson U.S. President. |

William Lumpkin Governor of Georgia |

||

| 1836 | John Ross Cherokee Leader |

|||

| 1837 | ||||

| 1838 | Dahlonega Mint Dahlonega Mint |

Ralph Waldo Emerson Letter |

Notice from the Georgia Journal

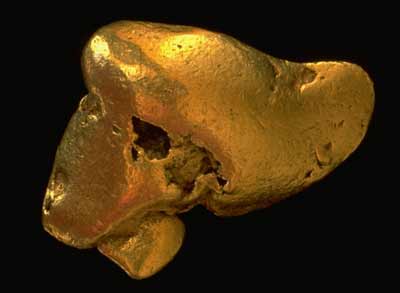

There is some debate about when gold was first discovered in Cherokee territory in the mountains of north Georgia. The article below from the Georgia Journal is one of the first announcements that led to an influx of placer miners to the rivers and streams settled by the Cherokee.

GOLD. A gentleman of the first respectability in Habersham county, writes us thus under date of 22d July: "Two gold mines have just been discovered in this county, and preparations are making to bring these hidden treasures of the earth to use." So it appears that what we long anticipated has come to pass at last, namely, that the gold region of North and South Carolina, would be found to extend into Georgia.

from David Williams, The Georgia Gold Rush, Columbus, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1993.

A Brief View of the Present Relations between the Government and People of the United States and the Indians within Our National Limits

The American Board of Commissions for Foreign Missions was responsible for establishing most of the church missions and schools among the Cherokee and other southern tribes. Jeremiah Evarts was its leader and here provides arguments against the Indian Removal Act pending in Congress in 1829.

In the various discussions, which have attracted public attention within a few months past, several important positions, on the subject of the rights and claims of the Indians, have been clearly and firmly established. At least, this is considered to be the case, by a large portion of the intelligent and reflecting men in the community. Among the positions thus established are the following: which, for the sake of precision and easy reference, are set down in regular numerical order.

1. The American Indians, now living upon lands derived from their ancestors, and never alienated nor surrendered, have a perfect right to the continued and undisturbed possession of these lands.

2. Those Indian tribes and nations, which have remained under their own form of government, upon their own soil, and have never submitted themselves to the government of the whites, have a perfect right to retain their original form of government, or to alter it, according to their own views of convenience and propriety.

3. These rights of soil and of sovereignty are inherent in the Indians, till voluntarily surrendered by them; and cannot be taken away by compacts between communities of whites, to which compacts the Indians were not a party.

4. From the settlement of the English colonies in North America to the present day, the right of Indians to lands in their actual and peaceable possession, and to such form of government as they choose, has been admitted by the whites; though such admission is in no sense necessary to the perfect validity of the Indian title.

5. For one hundred and fifty years, innumerable treaties were made between the English colonists and the Indians, upon the basis of the Indians being independent nations, and having a perfect right to their country and their form of government.

6. During the revolutionary war, the United States, in their confederate character, made similar treaties, accompanied by the most solemn guaranty of territorial rights.

7. At the close of the revolutionary war, and before the adoption of the federal constitution, the United States, in their confederate character, made similar treaties with the Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Choctaws.

8. The State of Georgia, after the close of the revolutionary war, and before the adoption of the federal constitution, made similar treaties, on the same basis, with the Cherokees and Creeks.

9. By the constitution of the United States, the exclusive power of making treaties with the Indians was conferred on the general government; and, in the execution of this power, the faith of the nation has been many times pledged to the Cherokees, Creeks, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and other Indian nations. In nearly all these treaties, the national and territorial rights of the Indians are guaranteed to them, either expressly, or by implication.

10. The State of Georgia has, by numerous public acts, implicitly acquiesced in this exercise of the treaty-making power of the United States.

11. The laws of the United States, as well as treaties with the Indians, prohibit all persons, whether acting as individuals, or as agents of any State, from encroaching upon territory secured to the Indians. By these laws severe penalties are inflicted upon offenders; and the execution of the laws on this subject, is specially confided to the President of the United States, who has the whole force of the country at his disposal for this purpose.

The positions here recited are deemed to be incontrovertible. It follows, therefore,

That the removal of any nation of Indians from their country by force would be an instance of gross and cruel oppression:

That all attempts to accomplish this removal of the Indians by bribery or fraud. by intimidation and threats, by withholding from them a knowledge of the strength of their cause, by practising upon their ignorance. and their fears, or by vexatious opportunities, interpreted by them to mean nearly the same thing as a command; all such attempts are acts of oppression, and therefore entirely unjustifiable:

That the United States are firmly bound by treaty to protect the Indians from force and encroachments on the part of a State; and a refusal thus to protect them would be equally an act of bad faith as a refusal to protect them against individuals: and

That the Cherokees have therefore the guaranty of the United States, solemnly and repeatedly given, as a security against encroachments from Georgia and the neighboring States. By virtue of this guaranty the Cherokees may rightfully demand that the United States shall keep all intruders at a distance, from whatever quarter, or in whatever character they may come. Thus secured and defended in the possession of their country the Cherokees have a perfect right to retain that possession as long as they please. Such a retention of their country is no just cause of complaint or offence to any State or to any individual. It is merely an exercise of natural rights which rights have been not only acknowledged but repeatedly and solemnly confirmed by the United States....

from Jeremiah Evarts, "A Brief View of the Present Relations between the Government and People of the United States and the Indians within Our National Limits" November 1829 in Theda Perdue, editor, The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995, pp 96-98.

from The Cherokee Phoenix

During the decade of the 1820s Cherokee leaders came to expect federal help against the intrusion of white settlers on their land as treaties required. With the election of Andrew Jackson as President, though, as Georgia passed laws to define the state's claim to Cherokee land, and particularly after the discovery of gold in northern Georgia help was not to be found.

Wednesday, February 4, 1829

We understand upon good authority that our frontier neighbours (sic) in Georgia are moving in fast and settling on the lands belonging to the Cherokees. Right or wrong they are determined to take the country

Attempts of this kind have been made heretofore, but without any success, for the intercourse law of the United States has been invariably executed. Whether the President will again use the military force to oust these intruders as the law provides, we are not able to say. The law is explicit, and we hope, for the honor of the General Government, it will be faithfully executed.- It is as follows:

- Sec. 5. And be it further enacted, That if any such citizen or other person, shall make a settlement on any lands belonging, or secured, or granted, by treaty with the United States, to any Indian tribe, or shall survey, or attempt to survey, such lands, or designate any of the boundaries, by marking trees or otherwise, such offender shall forfeit a sum not exceeding one thousand dollars, and suffer imprisonment, not exceeding twelve months. And it shall, moreover, be lawful for the President of the United States to take such measures, and to employ such military force, as he may judge necessary, to remove from lands, belonging, or secured by treaty as aforesaid, to any Indian tribe, any such citizen, or other person, who has made or shall hereafter make, or attempt to make, a settlement thereon.

There is one fact connected with this affair, which we think proper to mention. When known, in the view of every honest and liberal man, it ought to redound to the credit of the Cherokees. It is this. In all cases of intrusions, when whitemen (sic) have behaved in a provoking manner, and with the greatest degree of impudence, the Cherokees have never, to our knowledge, resorted to forcible measures, but have peaceably retired, and have patiently waited for the interference of the United States, and the execution of the above section. Does not this show that they are faithful to the treaty contracts, and that they expect the like faithfulness from the United States. We hope that they will not now be disappointed.

from The Cherokee Phoenix, Wednesday, February 4, 1829, Volume 1 No. 47, Page 2 Col. 3a-4a as found at The Cherokee Phoenix Special Collection in the Hunter Library, Western Carolina University.

A Report from the House Committee on Indian Affairs

The excerpts below are from a report by the Committee on Indian Affairs in the U. S. House of Representatives. It was issued in 1830 and formed part of the debate over the Indian Removal Act.

The most active and extraordinary means have been employed to misrepresent the intentions of the Government, on the one hand, and the condition of the Indians on the other. The vivid representations of the progress of Indian civilization, which have been so industriously circulated by the party among themselves opposed to emigration and by their agents, have had the effect of engaging the sympathies, and exciting the zeal, of many benevolent individuals and societies, who have manifested scarcely less talents than perseverance in resisting the views of the Government. Whether those who have been thus employed, can claim to have been the most judicious friends of the Indians, remains to be tested by time. The effect of these indications of favor and protection has been to encourage them in the most extravagant pretensions. They have been taught to have new views of their rights. The Cherokees have decreed the integrity of their territory, and claimed to be as sovereign within their limits, as the States are in theirs. They have actually asserted such attributes of sovereignty, as, if indulged, must subvert the influence, and effect a radical change of the policy and interests of the Government, in relation to their affairs. Some of the States, within whose limits those tribes are situated, have determined, by the exercise of their rights of jurisdiction within their territorial limits, to repress, while it may be done with the least inconvenience, a spirit which they foresee, may, in time, produce the most serious mischiefs. This exercise of authority by the States has been remonstrated against by those who control the affairs of the Indians, and application has been made to the Federal Government to interpose its authority in defence of their claim to sovereignty....

No respectable jurist has ever gravely contended, that the right of the Indians to hold their reserved lands, could be supported in the courts of the country, upon any other ground than the grant or permission of the sovereignty or State in which such lands lie....

The country which has heretofore been designated as proper to be allotted to the Indians, although not exhibiting the same variety of features with some portion of the country now occupied by them, possesses, in the outlet which it affords to a great western common and hunting ground, not likely to become the early abode of the white race, an advantage and relief to the adult Indians of the present generation, which, in the opinion of the committee, cannot be supplied in any other shape. If this country is secured to the Indians, or such portions of it as shall be satisfactory to them, it is believed the greatest objection will be removed which has heretofore existed with any portion of the more sagacious Indians, having no more than a common interest in remaining where they are, to the plan of emigration. If such measures shall be resorted to as will satisfy the Indians generally, that the Government means to treat them with kindness, and to secure to them a country beyond the power of the white inhabitants to annoy them, the influence of their chiefs cannot longer prevent their emigration. Looking to this event, it would seem proper to make an ample appropriation, that any voluntary indication, on the part of the Indians, of a general disposition to remove, may be seconded efficiently by the Government.

from Committee on Indian Affairs. Removal of Indians, Delivered in the House of Representatives, 21st Congress, 1st Session, 24 February, 1830 pp 2, 5-6, 25.

from Speech of Mr. Everett of Massachusetts

Debate on the Cherokee Removal Act in the U. S. House of Representatives followed the favorable report from the Committee on Indian Affairs. The division in the House is obvious in the excerpts from this speech by Massachusetts Congressman, Edward Everett.

Gentlemen, who favor the project [Indian removal], cannot have viewed it as it is. They think of a march of Indian warriors, penetrating with their accustomed vigor, the forest or the cane brake—they think of the youthful Indian hunter, going forth exultingly to the chase. Sir, it is no such thing. This is all past; it is matter of distant tradition, and poetical fancy. They have nothing now left of the Indian, but his social and political inferiority. They are to go in families, the old and the young, wives and children, the feeble, the sick. And how are they to go? Not in luxurious carriages; they are poor. Not in stagecoaches; they go to a region where there are none. Not even in wagons, nor on horseback, for they are to go in the least expensive manner possible. They are to go on foot: nay, they are to be driven by contract. The price has been reduced, and is still further to be reduced, and it is to be reduced, by sending them by contract. It is to be screwed down to the least farthing, to eight dollars per head. — A community of civilized people, of all ages, sexes and conditions of bodily health, are to be dragged hundreds of miles, over mountains, rivers, and deserts, where there are no roads, no bridges, no habitations, and this is to be done for eight dollars a head; and done by contract. The question is to be, what is the least for which you will take so many hundred families, averaging so many infirm old men, so many little children, so many lame, feeble and sick? What will you contract for? The imagination sickens at the thought of what will happen to a company of these emigrants, which may prove less strong, less able to pursue the journey than was anticipated. — Will the contractor stop for the old man to rest, for the sick to get well; for the fainting women and children to revive? He will not; he cannot afford to. And this process is to be extended to every family, in a population of seventy-five thousand souls. This is what we call the removal of the Indians!

It is very easy to talk of this subject, reposing on these luxurious chairs, and protected by these massy walls, and this gorgeous canopy, from the power of the elements. Removal is a soft word, and words are delusive. — But let gentlemen take the matter home to themselves and their neighbors. There are 75,000 Indians to be removed. This is not less than the population of two congressional districts. We are going, then, to take a population of Indians, of families, who live as we do in houses, work as we do in the field or the workshop, at the plough and the loom, who are governed as we are by laws, who send their children to school, and who attend themselves on the ministry of the Christian faith, to march them from their homes, and put them down in a remote unexplored desert. We are going to do it— this Congress is going to do it—this is a bill to do it. Now let any gentleman think how he would stand, were he to go home and tell his constituents, that they were to be removed, whole counties of them—they must fly before the wrath of insupportable laws—they must go to the distant desert, beyond Arkansas—go for eight dollars a head, by contract—that this was the policy of the Government—that the bill had passed—the money was voted—you had voted for it—and go they must.

from Edward Everett, "Speech of Mr. Everett, of Massachusetts, on the Bill for Removing the Indians from the East to the West Side of the Mississippi. Delivered in the House of Representatives, On the 19th of May, 1830," (Boston: Office of the Daily Advertiser, 1830) pp. 28, 35.

from A Letter Reprinted in the Cherokee Phoenix

In a series of laws during the 1820s Georgia extended its jurisdiction over the land claimed by the Cherokee nation. Wirt, a former U. S. Attorney General, presents a case against Georgia's jurisdiction in this 1830 letter.

Baltimore

June 20th, 1830.

...On every ground of argument on which I have been enabled by my own reflections, or the suggestions of others, to consider this question, I am of the opinion,

1. That the Cherokees are a sovereign nation; and that their having placed themselves under the protection of the United States does not at all impair their sovereignty and independence as a Nation. "One community may be bound to another by a very unequal alliance, and still be a sovereign State. Though a weak State, in order to provide for its safety, should place itself under the protection of a more powerful one, yet according to Vattell (B. I Ch. I § 5 and 6,) if it reserves to itself the right of governing its own body, it ought to be considered as an independent State." 20 Johnson's Report 711, 712 Goodell vs. Jackson.

2. That the territory of the Cherokees is not within the jurisdiction of the State of Georgia, but within the sole and exclusive jurisdiction of the Cherokee Nation.

3. That consequently, the State of Georgia has no right to extend her laws over that territory.

4. That the law of Georgia which has been placed before me, is unconstitutional and void, 1. because it is repugnant to the law of the United States passed in 1802, entitled "an act to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes and to preserve peace on the frontiers." 3. because it is repugnant to the constitution, inasmuch as it impairs the obligation of all the contracts arising under the treaties with the Cherokees: and affects moreover to regulate intercourse with an Indian tribe, a power which belongs exclusively to Congress.

WM. WIRT

from Removal of the Cherokee Indians, part of the Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842, GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830

The Indian Removal Act was the legal basis for negotiating treaties with the tribes of the southeastern United States resulting in their removal west of the Mississippi. President Andrew Jackson was the architect and chief proponent of the act that pushed the cause of settlers in the southern states, particularly in Georgia.

CHAP. CXLVIII.

An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That it shall and may be lawful for the President of the United States to cause so much of any territory belonging to the United States, west of the river Mississippi, not included in any state or organized territory, and to which the Indian title has been extinguished, as he may judge necessary, to be divided into a suitable number of districts, for the reception of such tribes or nations of Indians as may choose to exchange the lands where they now reside, and remove there; and to cause each of said districts to be so described by natural or artificial marks, as to be easily distinguished from every other.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to exchange any or all of such districts, so to be laid off and described, with any tribe or nation within the limits of any of the states or territories, and with which the United States have existing treaties, for the whole or any part or portion of the territory claimed and occupied by such tribe or nation, within the bounds of any one or more of the states or territories, where the land claimed and occupied by the Indians, is owned by the United States, or the United States are bound to the state within which it lies to extinguish the Indian claim thereto.

SEC. 3. And be it further enacted, That in the making of any such exchange or exchanges, it shall and may be lawful for the President solemnly to assure the tribe or nation with which the exchange is made, that the United States will forever secure and guaranty to them, and their heirs or successors, the country so exchanged with them; and if they prefer it, that the United States will cause a patent or grant to be made and executed to them for the same: Provided always, That such lands shall revert to the United States, if the Indians become extinct, or abandon the same.

SEC. 4. And be it further enacted, That if, upon any of the lands now occupied by the Indians, and to be exchanged for, there should be such improvements as add value to the land claimed by any individual or individuals of such tribes or nations, it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such value to be ascertained by appraisement or otherwise, and to cause such ascertained value to be paid to the person or persons rightfully claiming such improvements. And upon the payment of such valuation, the improvements so valued and paid for, shall pass to the United States, and possession shall not afterwards be permitted to any of the same tribe.

SEC. 5. And be it further enacted, That upon the making of any such exchange as is contemplated by this act, it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such aid and assistance to be furnished to the emigrants as may be necessary and proper to enable them to remove to, and settle in, the country for which they may have exchanged; and also, to give them such aid and assistance as may be necessary for their support and subsistence for the first year after their removal.

SEC. 6. And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such tribe or nation to be protected, at their new residence, against all interruption or disturbance from any other tribe or nation of Indians, or from any other person or persons whatever.

SEC. 7. And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to have the same superintendence and care over any tribe or nation in the country to which they may remove, as contemplated by this act, that he is now authorized to have over them at their present places of residence.

from A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875 Statutes at Large, 21st Congress, 1st Session, pp 411-412 part of the Library of Congress American Memory Project.

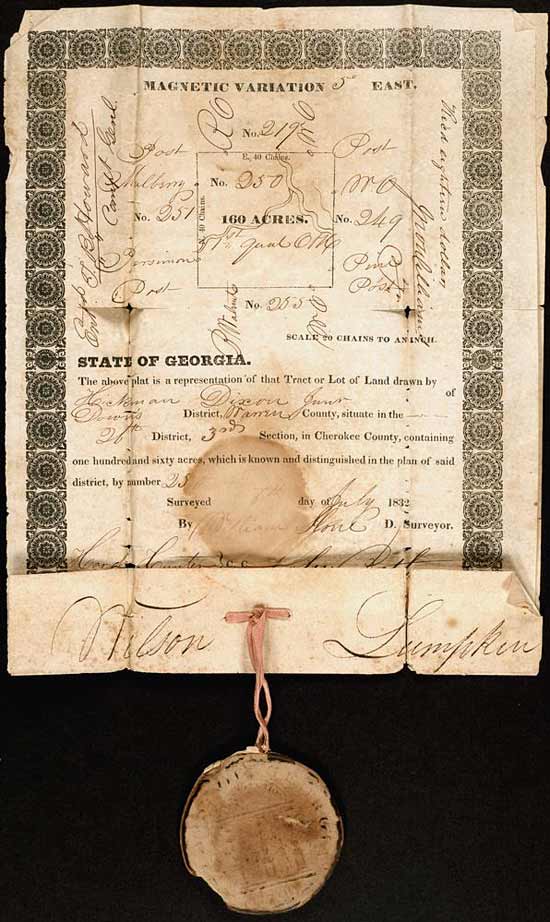

Georgia Land Grant

In 1832 the state of Georgia again made use of a lottery system it had used since 1805 to distribute public land - this time the land the state claimed in the Cherokee territory. Individual settlers purchased lottery tickets and tickets were then drawn from a barrel at random for lots of varying sizes (160 acres in the case of the ticket below). The drawings were frequently oversubscribed by the large numbers of would be settlers.

"Land grant with map for plot in Cherokee County, Georgia," Jan 7, 1833, authorized by Wilson Lumpkin, Governor of Georgia as found at Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842, GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

A Letter to Wilson Lumpkin, Governor of Georgia

Lumpkin served as a Georgia Representative in the U. S. Congress from 1827 to 1831 at the time the Indian Removal Act was debated and passed. He was Governor of Georgia from 1831 to 1835 and was the strongest possible advocate of Cherokee removal. In this letter from John Ridge to the Governor the depth of the split among the Cherokee leadership between the Ridge and Ross factions over the issue of removal is all too evident.

Cassville Ga

22d. Sept. 1833.

Dear Sir,

I have been in tending to write to you on the Indian Affairs for some time, but the press of business in conducting the business of our nation at this interesting period, has [deleted: been] prevented. I feel pleasure now to say that our cause prospers, & I believe will result in the general Cession of the Nation. The views taken in a communication by a Gentleman of the bar in the Georgia -- Pioneer on the Cherokee treaty, Should be republished with the correction of misprints in the paper alluded to. John Ross& his party will try to outlive the Administration of Genl. Jackson if they are not forced into the treaty, & it now depends upon the treaty party to take a bold and decided stand. We have gained so much now in Georgia & Alabama, that we shall soon organise head chiefs & a regular Council for those two states and close the treaty. However this is conditioned upon the refusal of the Ross party to Join in a general treaty -- He has requested a Conference, and we have accepted it, & it is possible that we may agree to make a General Cession. This Conference will be held it is proposed on the 2d. Monday in Oct. next in the chartered limits of Tennessee -- If that Council passes by with out our bringing the parties to an understanding, you may depend upon a vigorous course of measures on our part -- How shall we proceed?. It is plain that Indians hold title to Land by the right of occupancy & The Ross party chiefs are about to abandon this & go to Tennessee. We have chiefs & a Council & the President can acknowledge us & treat with us. In the meantime, and all the time the enrollment can go on I will go on which will give us thereby strength. From this purpose the next Legislature ought to pass laws to protect us in our possessions while we are in the act of preperation for the West. Unless this is done our efforts will prove abortive The U. S. promises this protection, but individual avidity to get possession of Indian Improvements, falsifies all these promises. As soon as an Indian enrolls he Georgia claimant presses him -- out -- this stops them from enrolling -- it gives them no time to -- breathe -- no comfort after it -- This should not be -- I know Sir, that by force of circumstances your state will get in possession of the -- whole of our Lands, but it will -- be with great suffering to the Indians. Our exertions will be crippled -- if a favorable legislation is not, had upon this very subject. It is nothing but -- what the dictates of humanity will sanction to allow the Indians to -- go off unmolested, when they evince a desire to do so by enrollment. I cannot close this letter without referring to the great good, which Col. Bishop -- & the Georgia Guard have effected. If the Legislature would grant him certain discretionary powers in relation to the Indians it would be of great service.

The Ross party tried hard to counteract the growth of our party by -- murders -- it is dreadful to reflect on -- the amount of blood which has been shed -- by the savages on those who have only exercised the right of -- opinion -- The Guard has been watchful & they have arrested these -- men who encourage the murders, & some of the murderers themselves. They see now that this course will not do. The amount of other crimes committed in this country is amazing, & I do sincerely believe that this Guard is necessary to be continued in this country until the treaty is consummated. If this guard was not in existence our labors would be inefficient compared to what they are. The lives of the emigrating party would be sacrificed, & also the lives of the citizens of Georgia would be in danger.

I can say that the prospects of a general treaty is flattering, but we must prepare for the work as good generals in time of war. Keep what we have & gain the balance. The officers of the U. S. in this country & myself wrote you a joint letter granting indulgence to the treaty party in their possessions while they remained according to the promises of the U.S. which I hope you have received before this.

Of course this letter is not for publication -- I shall write to you again --

your friend

John Ridge

from John Ridge, "Letter, 1833 Sept. 22, Cassville, Georgia, [to] Wilson Lumpkin, Gov. Georgia" as found at Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842, GALILEO Digital Library of Georgia.

Seventh Annual Message to Congress

In this passage from his annual message to Congress, President Jackson makes his case for the United States to look after its aboriginal children.

December 7, 1835

...The plan of removing the aboriginal people who yet remain within the settled portions of the United States to the country west of the Mississippi River approaches its consummation. It was adopted on the most mature consideration of the condition of this race, and ought to be persisted in till the object is accomplished, and prosecuted with as much vigor as a just regard to their circumstances will permit, and as fast as their consent can be obtained. All preceding experiments for the improvement of the Indians have failed. It seems now to be an established fact they can not live in contact with a civilized community and prosper. Ages of fruitless endeavors have at length brought us to a knowledge of this principle of intercommunication with them. The past we can not recall, but the future we can provide for. Independently of the treaty stipulations into which we have entered with the various tribes for the usufructuary rights they have ceded to us, no one can doubt the moral duty of the Government of the United States to protect and if possible to preserve and perpetuate the scattered remnants of this race which are left within our borders. In the discharge of this duty an extensive region in the West has been assigned for their permanent residence. It has been divided into districts and allotted among them. Many have already removed and others are preparing to go, and with the exception of two small bands living in Ohio and Indiana, not exceeding 1,500 persons, and of the Cherokees, all the tribes on the east side of the Mississippi, and extending from Lake Michigan to Florida, have entered into engagements which will lead to their transplantation.

The plan for their removal and reestablishment is founded upon the knowledge we have gained of their character and habits, and has been dictated by a spirit of enlarged liberality. A territory exceeding in extent that relinquished has been granted to each tribe. Of its climate, fertility, and capacity to support an Indian population the representations are highly favorable. To these districts the Indians are removed at the expense of the United States, and with certain supplies of clothing, arms, ammunition, and other indispensable articles; they are also furnished gratuitously with provisions for the period of a year after their arrival at their new homes. In that time, from the nature of the country and of the products raised by them, they can subsist themselves by agricultural labor, if they choose to resort to that mode of life; if they do not they are upon the skirts of the great prairies, where countless herds of buffalo roam, and a short time suffices to adapt their own habits to the changes which a change of the animals destined for their food may require. Ample arrangements have also been made for the support of schools; in some instances council houses and churches are to be erected, dwellings constructed for the chiefs, and mills for common use. Funds have been set apart for the maintenance of the poor; the most necessary mechanical arts have been introduced, and blacksmiths, gunsmiths, wheelwrights, millwrights, etc., are supported among them. Steel and iron, and sometimes salt, are purchased for them, and plows and other farming utensils, domestic animals, looms, spinning wheels, cards, etc., are presented to them. And besides these beneficial arrangements, annuities are in all cases paid, amounting in some instances to more than $30 for each individual of the tribe, and in all cases sufficiently great, if justly divided and prudently expended, to enable them, in addition to their own exertions, to live comfortably. And as a stimulus for exertion, it is now provided by law that "in all cases of the appointment of interpreters or other persons employed for the benefit of the Indians a preference shall be given to persons of Indian descent, if such can be found who are properly qualified for the discharge of the duties."

Such are the arrangements for the physical comfort and for the moral improvement of the Indians. The necessary measures for their political advancement and for their separation from our citizens have not been neglected. The pledge of the United States has been given by Congress that the country destined for the residence of this people shall be forever "secured and guaranteed to them." A country west of Missouri and Arkansas has been assigned to them, into which the white settlements are not to be pushed. No political communities can be formed in that extensive region, except those which are established by the Indians themselves or by the Untied States for them and with their concurrence. A barrier has thus been raised for their protection against the encroachment of our citizens, and guarding the Indians as far as possible from those evils which have brought them to their present condition. Summary authority has been given by law to destroy all ardent spirits found in their country, without waiting the doubtful result and slow process of a legal seizure. I consider the absolute and unconditional interdiction of this article among these people as the first and great step in their melioration. Halfway measures will answer no purpose. These can not successfully contend against the cupidity of the seller and the overpowering appetite of the buyer. And the destructive effects of the traffic are marked in every page of the history of our Indian intercourse. . . .

from Andrew Jackson. Seventh Annual Message to Congress, December 7, 1835.

A Letter by Wilson Lumpkin, Governor of Georgia

By 1835, having won his case for Indian removal in 1830 and with an ally in the White House in the person of Andrew Jackson, Governor Lumpkin of Georgia could call for a change in federal policy that offered protection for the remnants of the southeastern tribes.

May 4th 1835

To Eli S. Shorter, J.P.H. Campbell, and Alferd Iverson, Esqrs.

Gentlemen:

...It is true the President of the United States disclaims all right to intermeddle with the Government and jurisdiction of States, in regard to our Indian population, where the States have extended their laws and jurisdiction over these people. And while I most fully concur with the President, in denying the right of the Federal Government to impede or control the State authorities in an, manner whatever in relation to the government of these 'unfortunate people, I have, nevertheless, contended, and still believe, that it is the duty of the Federal Government to cooperate with the States in all just measures which may be calculated to speedily remove the evils of an Indian population from the States. In regard to our own State, it is wholly unnecessary for one, when addressing Georgians, to advert to the strong obligations which rest upon the Federal Government to relieve the State from the long-standing embarrassments and deeply injurious effects of an Indian population. It has been the settled convictions of my own mind, for years past (although not sustained by the public opinion of the country), that existing circumstances demanded from the Federal Government a radical change of policy in regard to the remnant tribes of the Cherokee and Creek Indians who still remain within the limits of the States. I consider it a perfect farce and degrading to the Government of the Union, under existing circumstances, to pretend any longer to consider or treat these unfortunate remnants of a once mighty race as independent nations of people, capable of entering into treaty stipulations as such. These conquered and subdued remnants deserve the magnanimous and liberal support and protection of the Government, and should be treated with tender regard, as orphans and minors who are incapable of managing and protecting their own patrimony. This course of policy, if pursued by the Federal Government, would soon relieve the States from the inquietudes of an Indian population, and settle the Indians in a land of hope where they would be shielded and protected from the enormous and degrading frauds which have been so often perpetrated on these sons of the forest by an avaricious and selfish portion of our white population....

from Wilson Lumpkin, The Removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia, New York: Arno Press, 1969, pp 339-340.

Letter To the Senate and House of Representatives

John Ross along with Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot had been the principle leaders of the Cherokee during the 1820s and early 30s. The following letter addressed to the U. S. Congress speaks to the division amongst the Cherokee over the issue of removal and the strong feelings on the part of the majority of the Cherokee against Ridge, Boudinot , and the small group who had negotiated the Treaty of New Echota.

Red Clay Council Ground, Cherokee Nation

September 28, 1836

It is well known that for a number of years past we have been harassed by a series of vexations, which it is deemed unnecessary to recite in detail, but the evidence of which our delegation will be prepared to furnish. With a view to bringing our troubles to a close, a delegation was appointed on the 23rd of October, 1835, by the General Council of the nation, clothed with full powers to enter into arrangements with the Government of the United States, for the final adjustment of all our existing difficulties. The delegation failing to effect an arrangement with the United States commissioner, then in the nation, proceeded, agreeably to their instructions in that case, to Washington City, for the purpose of negotiating a treaty with the authorities of the United States.

After the departure of the Delegation, a contract was made by the Rev. John F. Schermerhorn, and certain individual Cherokees, purporting to be a "treaty, concluded at New Echota, in the State of Georgia, on the 29th day of December, 1835, by General William Carroll and John F. Schermerhorn, commissioners on the part of the United States, and the chiefs, headmen, and people of the Cherokee tribes of Indians." A spurious Delegation, in violation of a special injunction of the general council of the nation, proceeded to Washington City with this pretended treaty, and by false and fraudulent representations supplanted in the favor of the Government the legal and accredited Delegation of the Cherokee people, and obtained for this instrument, after making important alterations in its provisions, the recognition of the United States Government. And now it is presented to us as a treaty, ratified by the Senate, and approved by the President, and our acquiescence in its requirements demanded, under the sanction of the displeasure of the United States, and the threat of summary compulsion, in case of refusal. It comes to us, not through our legitimate authorities, the known and usual medium of communication between the Government of the United States and our nation, but through the agency of a complication of powers, civil and military.

By the stipulations of this instrument, we are despoiled of our private possessions, the indefeasible property of individuals. We are stripped of every attribute of freedom and eligibility for legal self-defence. Our property may be plundered before our eyes; violence may be committed on our persons; even our lives may be taken away, and there is none to regard our complaints. We are denationalized; we are disfranchised. We are deprived of membership in the human family! We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own. And this is effected by the provisions of a compact which assumes the venerated, the sacred appellation of treaty.

We are overwhelmed! Our hearts are sickened, our utterance is paralized, when we reflect on the condition in which we are placed, by the audacious practices of unprincipled men, who have managed their stratagems with so much dexterity as to impose on the Government of the United States, in the face of our earnest, solemn, and reiterated protestations.

The instrument in question is not the act of our Nation; we are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people. The makers of it sustain no office nor appointment in our Nation, under the designation of Chiefs, Head men, or any other title, by which they hold, or could acquire, authority to assume the reins of Government, and to make bargain and sale of our rights, our possessions, and our common country. And we are constrained solemnly to declare, that we cannot but contemplate the enforcement of the stipulations of this instrument on us, against our consent, as an act of injustice and oppression, which, we are well persuaded, can never knowingly be countenanced by the Government and people of the United States; nor can we believe it to be the design of these honorable and highminded individuals, who stand at the head of the Govt., to bind a whole Nation, by the acts of a few unauthorized individuals. And, therefore, we, the parties to be affected by the result, appeal with confidence to the justice, the magnanimity, the compassion, of your honorable bodies, against the enforcement, on us, of the provisions of a compact, in the formation of which we have had no agency.

from Gary E. Moulton, editor, from Chief John Ross, vol 1, 1807-1839, Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985.

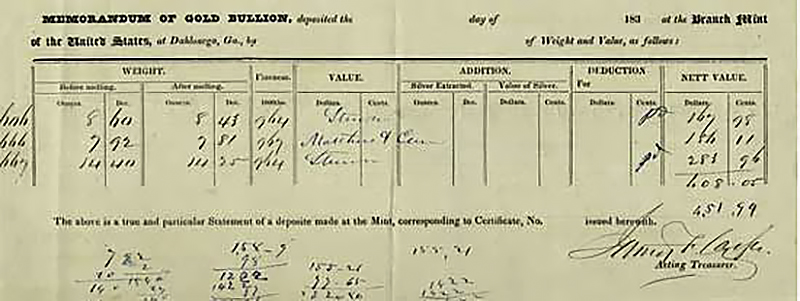

Memorandum of Gold Bullion Deposit - Dahlonega Mint

In 1835 Congress chartered three mints throughout the southern states including one at Dahlonega in the heart of the north Georgia gold fields and in territory ceded by the Cherokee in the Treaty of New Echota. The mint was completed in 1838 a year prior to Cherokee removal. The memorandum below documents a deposit to the mint.

"Memorandum of gold bullion [1838?]," from "Thar's Gold in Them Thar Hills": Gold and Gold Mining in Georgia, 1830s-1940s," in the Digital Library of Georgia, Document: mka056.

from A Letter to President Martin Van Buren

The job of actually removing the Cherokee following the Treaty of New Echota fell to President Martin van Buren when he succeeded Andrew Jackson. He also became the recipient of letters like the one below from Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson's passion for the cause is obvious and provides a preview of New England abolitionist arguments over the next two decades.

CONCORD, MASS.

April 23, 1838.

TO MARTIN VAN BUREN

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

SIR:

...Sir, my communication respects the sinister rumors that fill this part of the country concerning the Cherokee people. The interest always felt in the aboriginal population - an interest naturally growing as that decays - has been heightened in regard to this tribe. Even in our distant State some good rumor of their worth and civility has arrived. We have learned with joy their improvement in the social arts. We have read their newspapers. We have seen some of them in our schools and colleges. In common with the great body of the American people, we have witnessed with sympathy the painful labors of these red men to redeem their own race from the doom of eternal inferiority, and to borrow and domesticate in the tribe the arts and customs of the Caucasian race. And notwithstanding the unaccountable apathy with which of late years the Indians have been some-times abandoned to their enemies, it is not to be doubted that it is the good pleasure and the understanding of all humane persons in the Republic, of the men and the matrons sitting in the thriving independent families all over the land, that they shall be duly cared for ; that they shall taste justice and love from all to whom we have delegated the office of dealing with them.

The newspapers now inform us that, in December, 1835, a treaty contracting for the exchange of all the Cherokee territory was pretended to be made by an agent on the part of the United States with some persons appearing on the part of the Cherokees; that the fact afterwards transpired that these deputies did by no means represent the will of the nation; and that, out of eighteen thousand souls composing the nation, fifteen thousand six hundred and sixty-eight have protested against the so-called treaty. It now appears that the government of the United States choose to hold the Cherokees to this sham treaty, and are proceeding to execute the same. Almost the entire Cherokee Nation stand up and say, " This is not our act. Behold us. Here are we. Do not mistake that handful of deserters for us ; " and the American President and the Cabinet, the Senate and the House of Representatives, neither hear these men nor see them, and are contracting to put this active nation into carts and boats, and to drag them over mountains and rivers to a wilderness at a vast distance beyond the Mississippi. And a paper purporting to be an army order fixes a month from this day as the hour for this doleful removal.

In the name of God, sir, we ask you if this be so. Do the newspapers rightly inform us? Men and women with pale and perplexed faces meet one another in the streets and churches here, and ask if this be so. We have inquired if this be a gross misrepresentation from the party opposed to the government and anxious to blacken it with the people. We have looked in the newspapers of different parties and find a horrid confirmation of the tale. We are slow to believe it. We hoped the Indians were misinformed, and that their remonstrance was premature, and will turn out to be a needless act of terror.

The piety, the principle that is left in the United States, if only in its coarsest form, a regard to the speech of men, - forbid us to entertain it as a fact. Such a dereliction of all faith and virtue, such a denial of justice, and such deafness to screams for mercy were never heard of in times of peace and in the dealing of a nation with its own allies and wards, since the earth was made. Sir, does this government think that the people of the United States are become savage and mad? From their mind are the sentiments of love and a good nature wiped clean out? The soul of man, the justice, the mercy that is the heart in all men, from Maine to Georgia, does abhor this business.

In speaking thus the sentiments of my neighbors and my own, perhaps I overstep the bounds of decorum. But would it not be a higher indecorum coldly to argue a matter like this? We only state the fact that a crime is projected that confounds our understandings by its magnitude, - a crime that really deprives us as well as the Cherokees of a country? For how could we call the conspiracy that should crush these poor Indians our government, or the land that was cursed by their parting and dying imprecations our country, any more? You, sir, will bring down that renowned chair in which you sit into infamy if your seal is set to this instrument of perfidy; and the name of this nation, hitherto the sweet omen of religion and liberty, will stink to the world...

I write thus, sir, to inform you of the state of mind these Indian tidings have awakened here, and to pray with one voice more that you, whose hands are strong with the delegated power of fifteen millions of men, will avert with that might the terrific injury which threatens the Cherokee tribe.

With great respect, sir, I am your fellow citizen,

RALPH WALDO EMERSON.

from Ralph Waldo Emerson, " Letter to President Van Buren," at RWE.org - The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson - Volume XI - Miscellanies (1884) .

Removal Debate

1) In 1836 Vice President Martin Van Buren was elected President following Andrew Jackson's second term and was left with carrying out the provisions of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. Write a letter to the President arguing either for or against the continuation of Jackson's Indian policies. In your argument use any of the reading materials to rebut arguments made on the other side of the issue.

2) The U.S. Constitution provides that all treaties entered into by the President be approved by the Senate before they take effect. Use the materials above as the basis for a Senate debate over the 1835 Treaty of New Echota.

3) A group of Cherokee under the leadership of John Ridge and Elias Boudinout reluctantly came to the conclusion that removal was the best course of action for the tribe. Write a letter to the Cherokee Phoenix in which you argue their case. Use any of the other available materials to support your argument.