GIS in the History Classroom

In the Classroom - Teaching with GIS

There are two things in life we do alone. The second is to die and the first is to learn math.

This claim made by a colleague from the 1980s still echoes in my mind. How many teachers do you know who hold firmly to this point of view today - whatever the discipline; who would deny any advantage in treating learning as a social, not simply an individual, activity? There most certainly are times when students benefit from learning alone. Absorbing a teacher’s video lecture, engaging in drill and practice with a newly acquired skill, or writing an essay come to mind. There are, however, benefits gained from acknowledging that we are social beings and that there are highly effective teaching strategies that exploit this fact - strategies that are particularly well suited for students using GIS software.

David Jonassen ( 1996 ) has described software tools like GIS as mindtools:

...computer applications that, when used by learners to represent what they know, necessarily engage them in critical thinking about the content they are studying.

One of the principle advantages of software of this sort - be it spreadsheet, visualization tool, database, concept mapping app, or GIS software - is that when used in the social context of cooperative groups in the classroom it becomes a catalyst for inquiry and student shared, teacher moderated construction of meaning about new content and ideas. Concept learning - as opposed to procedural learning - is essentially a process of language development. We learn new ideas best by assimilating them into existing knowledge; that is, by attaching new vocabulary to both the new concepts and to the links between old and new ideas, sensations, and emotions. We build meaning, or gain fluency, largely by trial and error as the vocabulary and grammar of the new idea evolve through trial use, revision, and eventual assimilation into existing knowledge and language patterns. While writing - largely an individual activity - serves this purpose well in the latter stages of building meaning and, indeed, helps to build deeper understanding, structured conversation - a social activity - is particularly effective in the early stages of learning new material. Learning with GIS fits well into this model.

Working with student teachers over the years I encouraged experimentation with different strategies for teaching the same material. Use a lecture, use an inquiry activity, use group work, etc. Just teach to the same content and see how things go. This is a particularly effective way of getting prospective teachers to be more aware of their preferred style(s), their personal strengths and weaknesses, and, most importantly, to realizing that students have different learning styles and that a diversity of approaches is a necessity if you want to reach as many as possible. A variant on this experiment is a contest of sorts. Use different approaches to using computers and software like GIS in the classroom: one-on-one computing vs. students working in groups of two or three at one computer station. I have had student teachers try this experiment with two different sections of the same high school class and I have conducted the experiment myself with classes of pre service teachers and in workshop settings with inservice teachers. The goal in all cases is a pair of simple object lessons:

| • | Computers and the access they provide to both information and the tools for manipulating that information are in themselves very effective for promoting the type of social interaction that leads to focused discussion and to new concept formation. |

| • | One-on-one use of computers for a lesson in which students are expected to comfortably use a particular software and to engage new material with some degree of abstraction is often times counter productive. Even if it were possible to answer all of the technical questions that a large class of students working individually can generate, the amount of time left to guide students conceptually through new content would be minimal. |

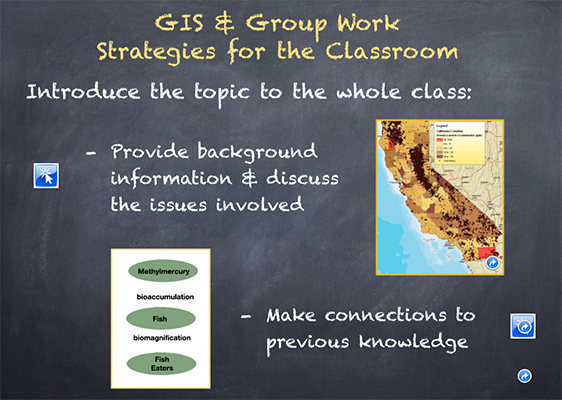

The lesson suggested in the plan outlined at right and featured in the slide presentation below provides an example of both the logistics of managing a group based lesson using GIS and exploring new content. Graphic links to specific lesson materials are included. The lesson is part of a unit in environmental history that looks at the impact of gold mining in the Mother Lode region of California and follows on a lesson about another toxic residue of the gold mining era: mercury.

Having students work in small, cooperative groups is a key to the success of the assignment. Questions coming from individual students working independently about computer and software use, about lesson directions, and about what is expected tend to fly furiously and can easily overwhelm the most patient teacher. Most such questions, though, are ones that groups of students can usually take care of by themselves freeing you to focus on dialog around the actual content of the lesson. Ideas in the presentation are based primarily on the personal experience of the author and on research by Radinski ( 2008 ) and Hammond ( 2009 ).

As you review the lesson plan it is worth keeping in mind the variety of factors that contribute to effective cooperative learning. Johnson & Johnson (1994) identify five significant characteristics. Their relevance to the Arsenic lesson is noted:

| • | Positive interdependence - there is a clear group goal - Each student, since one will be chosen at random, must be prepared to lead class discussion of the group’s inquiry into the correlation between an assigned type of cancer and arsenic levels in California counties and to field questions from classmates and the teacher. Collect all of the groups notes, maps, and summaries together so that there is clear evidence the group was working together. |

| • | Individual and group accountability - share the effort, share the reward - Johnson & Johnson suggest making one student in each group a “checker” - a person who reviews notes, who asks about the specific rationale for arguments developed as the group works, who monitors that each role in the group is being served and determines when it is time to switch roles. |

| • | Promotive interaction - students need to support one another - Each group member is expected to help the others in the group deal with the mechanics of the assignment, but more importantly serving as mutual sounding boards as they explore new ideas and build connections to old. |

| • | Teaching students small group skills - is ongoing - Continually reinforce and model positive cooperative behaviors (paraphrasing, asking clarifying questions, etc.) |

| • | Group processing - the easiest aspect of cooperative learning for me (and I suspect many teachers) to overlook - Have students spend a few minutes reflecting on how their group could have dealt with the assignment more effectively and what they did particularly well to help each other get the most out of the assignment. |